“Voice of Cards:” The Spoiler-Free Review

The latest game from the mind of Yoko Taro stuns with creative visual design and clever writing, but is bogged down by lackluster combat.

Voice of Cards has absolutely stunning assets, but they are stretched thin over a game that simultaneously feels too short and too long.

February 4, 2022

Welcome to Voice of Cards…

Unseen hands shuffle a deck of cards, laying them out on an ornate table as a soft piano plays and our narrator begins to monologue. These are the opening sights of “Voice of Cards: The Isle Dragon Roars,” Square Enix’s newest original project, first released on Oct. 28.

Just over a month after its release date was announced, the title was out on the Nintendo Eshop and Playstation Store, with the full game picking up five minutes from the end of the demo. As a whole, “Voice of Cards” took the demo’s systems and gave them greater depth, creating an immersive story with endearing characters and entertaining plot beats.

The story opens with a perspective shift from the demo, changing focus from the honored, altruistic, and incredibly dull Ivory Order members to Ash, a snarky mercenary motivated entirely by the promise of riches. In this opening stage of the game, the player is also introduced to Mar, Ash’s monstrous companion, and Melanie, a witch with a grudge against the dragon that the Ivory Order wants hunted down.

This fellowship begins their adventure across the Isle to track down this dragon, travelling through such standard locations: A Dark Cave, A Nonspecific Desert, A Misty Forest, An Idyllic Town with a Horrible Secret, Volcano, and of course, Evil Church, to name a few. There is also no shortage of menacing monsters to act as a never ending row of speed bumps between the “Would Be Adventurer” and his draconic quarry. The monsters have a more striking visual direction compared to their habitats, with lead artist Kimihiko Fujisaka offering unique takes on slimes, orcs, golems, skeletons, and other RPG fodder. The character design is also beautiful, with the immense detail in the main characters’ design, comparable to something you’d see in the manual of a game from 2002. The NPCs are also well designed, though not to the level of the main cast, as many of the townspeople are reused from one town to the next.

“Voice of Cards” has a very unique script, taking a storytelling style more comparable to a tabletop roleplaying game than any video game. The game has a single voice actor, Todd Haberkorn, in English and Hiroki Yasumoto in Japanese, playing the Game Master — a figure that acts as narrator, tutor, and performer for each and every character within the game. Such a limited cast required heavy lifting from Haberkorn and Yasumoto, but both voice actors delivered in spades, offering a contrasting performance. Yasumoto narrates with an air of grandeur around the story he tells, spelling out each detail to the player, while Haberkorn has a drier delivery that smooths out the cheesier moments in the story, showing a Game Master who is fully aware of how bizarre the story he is telling can get. The writing for the other characters is also incredibly entertaining, from the central cast’s bickering and bonding to the strange statements of random villagers.

The game’s story is still simple and linear, split into seven chapters separated by short cutscenes that recap the events of the previous chapter and foreshadow the next. Each chapter is told straightforwardly, with a swath of unexplored terrain on the map, a town with an item shop, armorer, apothecary, game parlor, carriage stop for fast travel, and a plot-important location with a gaggle of NPCs ready to exposit about the town in which they live. This isn’t to say the story is flat — there’s noticeable escalation from chapter to chapter, each dungeon gets bigger, each attack gets more dramatic, each boss gets beefier, and the plot keeps raising the stakes.

The game’s battle system is nothing special, even compared to the likes of other turn based games. Each character has a set of commands, categorized as elemental magic that can inflict status effects, attacks that hit all enemies, single-target attacks that don’t cost mana, or some abilities that heal and increase the stats of allies. Predictably, the enemies have similar attacks, though most of the enemies have stats so low that they barely scratch your party, leading to the battles having very little real impact. Some attacks also have different damage calculations, with some based solely on the attack stat, some adding a dice roll to attack, some relying only on the roll of a die, and some just dealing a flat amount of damage. There is also the aspect of elemental damage, which is balanced by certain monsters having variable weakness and resistances to different kinds of damage. This, along with status effects, limited loadout between 4 skills per party member and 3 party members at a time, and the limited supply of mana gems can lead to some creativity in dealing with the present monsters as quickly as possible.

However, despite the amazing art direction and storyline, the greatest flaw this game has is it’s utterly broken encounter rate. The player can hardly go seven spaces on the overworld or within a dungeon without the familiar “An Enemy Appears!” card going up and a slow-as-molasses battle with some monsters, the battle ending and the party returning to the map slightly worse for wear. Battles aren’t the only random encounter in this game. — there are also random encounters of the (mostly) nonviolent kind, including a pop-up merchant with discounted prices and uncommon items, environmental hazards like spontaneous lightning storms and avalanches, or thieves whispering about where they hid a rare item. These encounters offer a break from the constant stream of slow battles, but they are few and far between, and only take place on the overworld, outside of the dungeons.

While the game’s battles are incredibly slow, they are undeniably flashy — slowly flashy. The cards are quite dynamic, despite being unchanging rectangular images. For example, a card turns onto its side to chop an opponent, or slowly lumber forward for a high-powered attack. These card movements carry on into the story, with cards tilting downwards as they bow, turning upside down when knocked over, or splitting in half when their subject perishes. Battle animations are also very flashy, with intense particle effects and dramatic card movements that are simply stunning.

The music in this game’s soundtrack was a triumph from Keiichi Okabe and Oliver Good, combining chipper fantasy vibes with a touch of the musical tragedy that has become Okabe’s artistic fingerprint. The soundtrack initially seems fairly simple, with a strings and piano led soundtrack with very few tracks, one overworld theme, a single theme for every town, a dungeon theme, and music for the boss fight at the end of each dungeon. However, halfway through the game, the soundtrack reveals its hand, delivering an absolute masterpiece for the Dragon’s theme, soon followed up by an entirely new theme for the game’s second act, which takes the story in a much darker direction.

While the game is split into seven chapters, the final two chapters mark a tonal shift, changing the setting and the theme used for each chapter’s introduction. This final act is also when the penny drops on the mysteries that were hinted at throughout the story, making the game good enough to be played, despite its shortcomings.

All in all, “Voice of Cards: The Isle Dragon Roars” begins as a laid-back experience reminiscent of playing “Dungeons and Dragons,” though lacking the deeper roleplay, but insistent on showing you the depth of a very shallow combat system. The storytelling is campy and lighthearted, not taking itself too seriously, but the second act leads to a shift, with battles becoming more demanding and the plot taking a similar turn. Overall, the player must make their own fun in “Voice of Cards,” finding enjoyment in the combat, in the story, and in the characters, all of which are lacking in certain ways, be it depth, detail, or likability.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

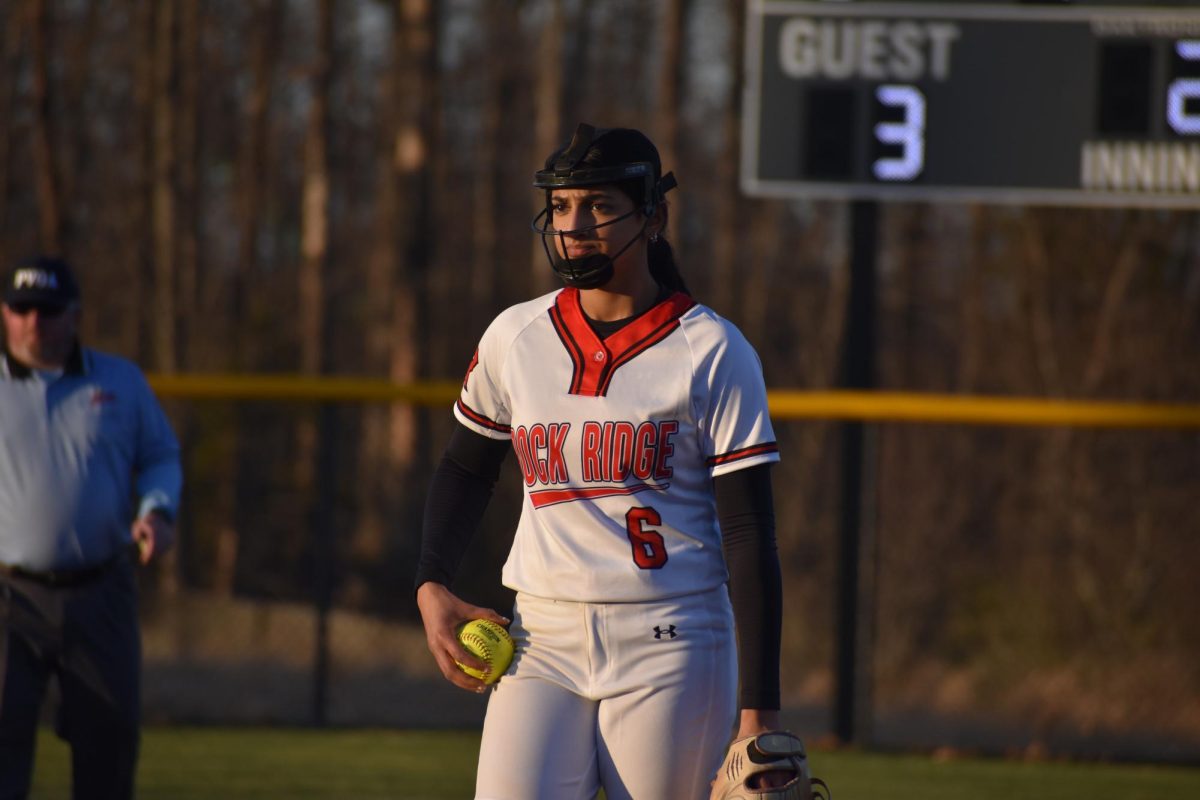

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)