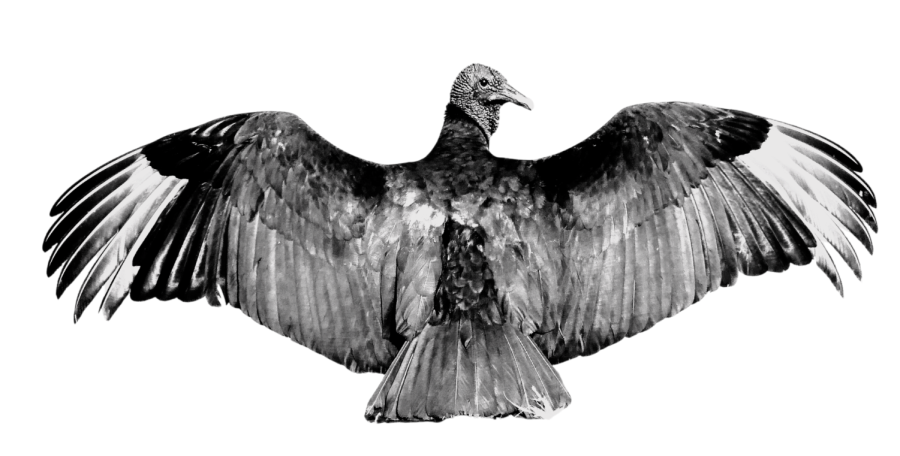

Should I Care About Vultures? The Fluctuating Population of Carrion-Eating Raptors

From the booming population of the black vulture to the historical critical endangerment of the California condor, raptors have been a topic of interest among ornithologists and conservation biologists alike. These population fluctuations can be tied to more anthropogenic factors than meets the eye.

Graphic by Kaleb Ryans; image by Bernard Dupont via Wikimedia Commons

Due to the highly sociable and intelligent nature of black vultures, they are almost never scared by usual nonlethal pest control tactics, such as bright lights, loud noises, or attempting to intimidate them, which likely exacerbates the incentive to use sublethal or completely lethal force.

Vultures have been rightfully identified as nature’s most effective scavenger. However, in more recent years, they have been sitting at either two extremes: killing young livestock, digging in trash heaps, and enjoying large landfills –common behavioral characteristics of black vultures—or ingesting lead poisoning, pesticides, and facing gruesome powerline electrocution. Farmers have started to kill and actively hunt down vultures to protect their farms, ignoring the anthropogenic factors that both threaten California condors and foster the survival of black vultures. The remedial approach to such a complex problem will not only prove as a major detriment to ecosystems, but also belies the lack of true deliberation within farmer and ornithological societies that is so essential to problem solving.

Lethal methods for controlling the vulture population have been supported by most farmers and rural communities, but how credible are they, and how can we understand their point of view? To start, the increasing black vulture population in the northern states has been more than a surprise to locals, due to their complete lack of presence just decades ago. These birds are, supposedly, now posing a threat to farmers, killing newborn livestock and possibly even their mothers. Along with claims of heightened aggression, these farmers have had considerable difficulty shooing them away—and they are more than ready to shoot and kill vultures to “protect” their animals. However, the recently retired director of The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, John W. Fitzpatrick, is skeptical. In a New York Times article published September of last year, he argues that the birds have only often targeted dead or dying calves. “The idea that they are predatory is false,” Fitzpatrick said.

While it is also true that their protection under the Migratory Bird Act can complicate this process for farmers, a solution as remedial as killing them off will only lead to ecosystem collapse and at worst, extreme disease outbreaks. To further refute this argument, though their appearance may seem sudden, the reality lies in major environmental influences—such as the gradual increase in municipal solid waste (MSW) produced by humans per day—fostering their stay in the northern regions of the United States.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the amount of MSW generated by Americans per day was around 5 pounds in 2018. Black vultures, among the turkey or California condor, are known to eat tens of pounds of carrion flesh and waste scraps per day. According to Audubon’s black vulture field guide, they have only benefited from climate change. Depending on the season, black vultures can gain up to 21% more range and maintain 100% range in a 1.5C-3C warming scenario in the summer. During the winter, these raptors can only lose as much as 1% of their range, can gain up to 27%, and are even guaranteed to maintain 99%. Without gradual change in our environment, following the aforementioned data, vulture populations will continue to rise.

To expand upon this, the current predicament with vultures is a key example of an indirect consequence of climate change. Vultures, among other raptors, use thermals to conserve energy and circle in the air for long periods of time. These thermals are caused by hot air fluctuations and uneven heating of the earth, which is certainly exacerbated due to global warming. The increase of hot land environments causes air to warm more rapidly and frequently, providing a much more suitable environment during winter seasons for raptors like the vulture.

While anthropogenic factors have been proving beneficial for black and turkey vultures, the survival of their close relatives, the California condors, have only worsened in consequence. Though vultures are capable of consuming large amounts of garbage and waste, their ability to break down substances with a low pH stomach acid can often spell their end. Pesticides such as DDT can easily ravage raptor populations, but it’s even more extreme for California condors due to their biological makeup. Other major factors toward their endangerment include environmental hazards like power lines or even wind turbines, and while less prevalent in nature, the total death toll continues to rise.

California condors are especially infamous for their dwindling population. Condors were declared extinct in 1987, and later since reemerged as only around two dozen left; and due to their birthing patterns, they have been replenishing their population at a slower rate than desired. Though conservationists have tried several strategies to increase their reproductive success, the rate of their extinction has continued to rise.

Conservation organizations have targeted primary causes of condor deaths, winning several court cases banning the use of lead ammunition for hunting and the destruction of habitats by logging companies. Though these efforts have been rather localized to southern states, conservationists hope the legislation will prove beneficial to not only raptors, but the environment as a whole.

To understand why the extreme fluctuations of either bird is problematic, we need to put the actions of the people under scrutiny. American locals have professed many grievances; however, too many have seemed to forget these anthropogenic factors, and have attributed all blame to these birds. The result of this denial, this mental block, has proven extremely detrimental to societies unknowingly reliant on these scavengers. The poaching and poisoning of Old World vultures in places like India have ended up ravaging human populations due to high influxes of rabies.

But how can we delay the spread of their range in our cities and farms without using lethal force? Although the most effective method has been the use of effigies, their proclivity to devour even other vulture carcasses proved to be its weakness. Few farmers have been experimenting with more effective methods, and at best, completely non-lethal methods. So far, very little has come close to the effectiveness of the effigy when it comes to harm reduction.

After studying the available data, one is still left with the question: what can we as individuals do about it? Unfortunately, while all hope is not lost, possible efforts are predicated entirely upon the willingness and cooperation of the common people. Donating to local conservation organizations, tracking your carbon emissions, and spreading awareness are all ways to help protect local bird species. Considering our access to modern technology, these efforts are a lot more individually achievable than one might think, especially with applications such as Wren.

However, at its core, this problem encompasses climate change, and is going to take more than individual effort. Whether the protection of these birds or the culling of them may be clear, the reduction of this overall widespread restlessness unarguably requires cautious contemplation.

Kaleb is a sophomore and this is his first year on staff. Kaleb likes to read, write, and play games recreationally. Kaleb uses a lot of personal experiences and thoughts to fuel his creative writing,...

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

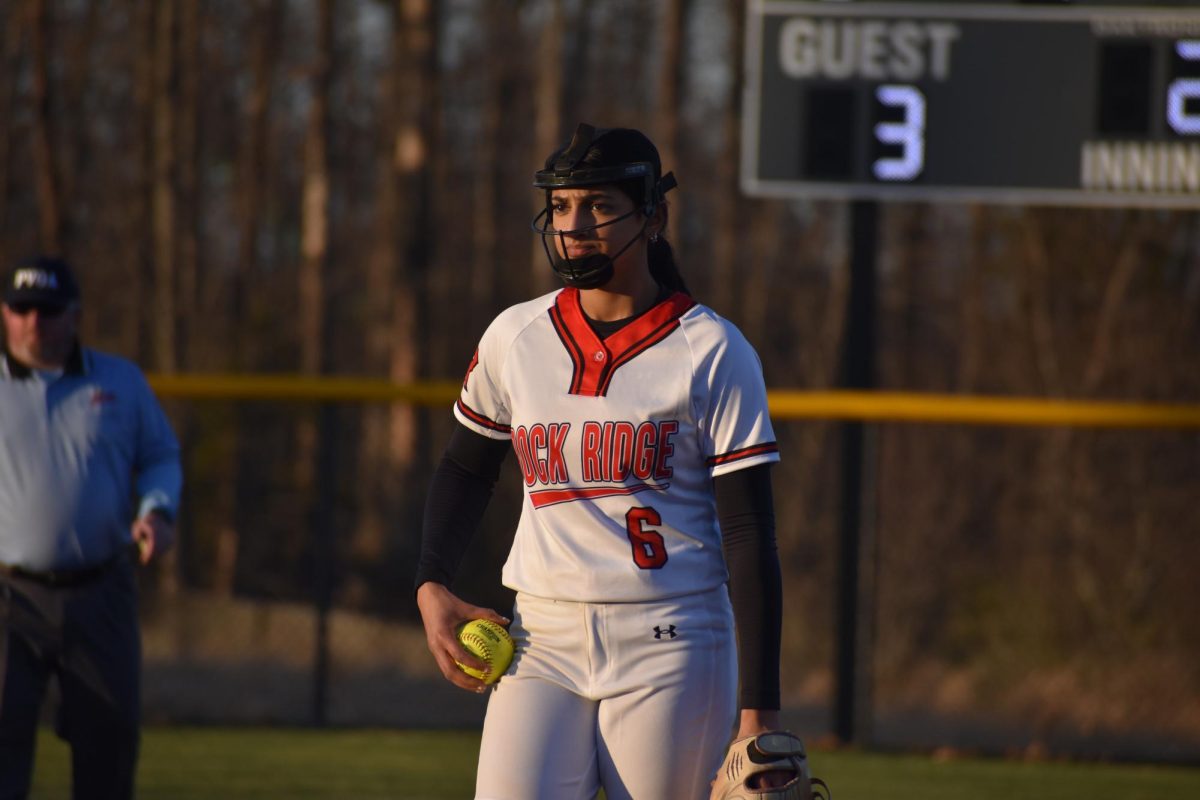

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)