Rock Ridge Recycling: The Unknown Crisis

For years now, Rock Ridge has supposedly mixed trash and recycling. Students and staff have been troubled with how to effectively solve this dilemma; but as recent information surfaces, new avenues to alleviate this issue are discovered.

Trash and recycling are categorized in groups for a reason—they were never meant to be mixed. However, due to recent technological advances, some areas within the U.S. are vying for mixed waste systems as more efficient and lucrative alternatives.

April 7, 2022

As students and staff return to in-person education, more and more individuals realize that just because containers in their classrooms are big, blue, and have a recycling label, it does not mean that they constitute as proper recycling bins. Giant blue bins in the cafeteria are filled to the brim with mixed waste–apple cores, juice boxes, paper containers–and at worst, perfectly edible food.

This intermixing of trash in schools is often attributed to students, as they spend their free time indulging in what leisure they can—and considering the carefree nature of a considerable margin of these students, it’s no surprise that waste ends up in the wrong bins. The issue with placing blame solely on students, however, is the lack of precedent recycling holds within schools in the first place.

Take what is expected of people to keep in mind each day: few types of waste–like paper, tin cans, aluminum, and glass–are all sorted in different bins in different areas, and what is deemed recyclable in Ashburn is likely different for Sterling. LCPS schools have made an effort to minimize this confusion by creating blue bins for all recyclables, eliminating the need to separate them into different bins. However, the major flaw with this remedial approach is the apparent absence of these bins in each classroom.

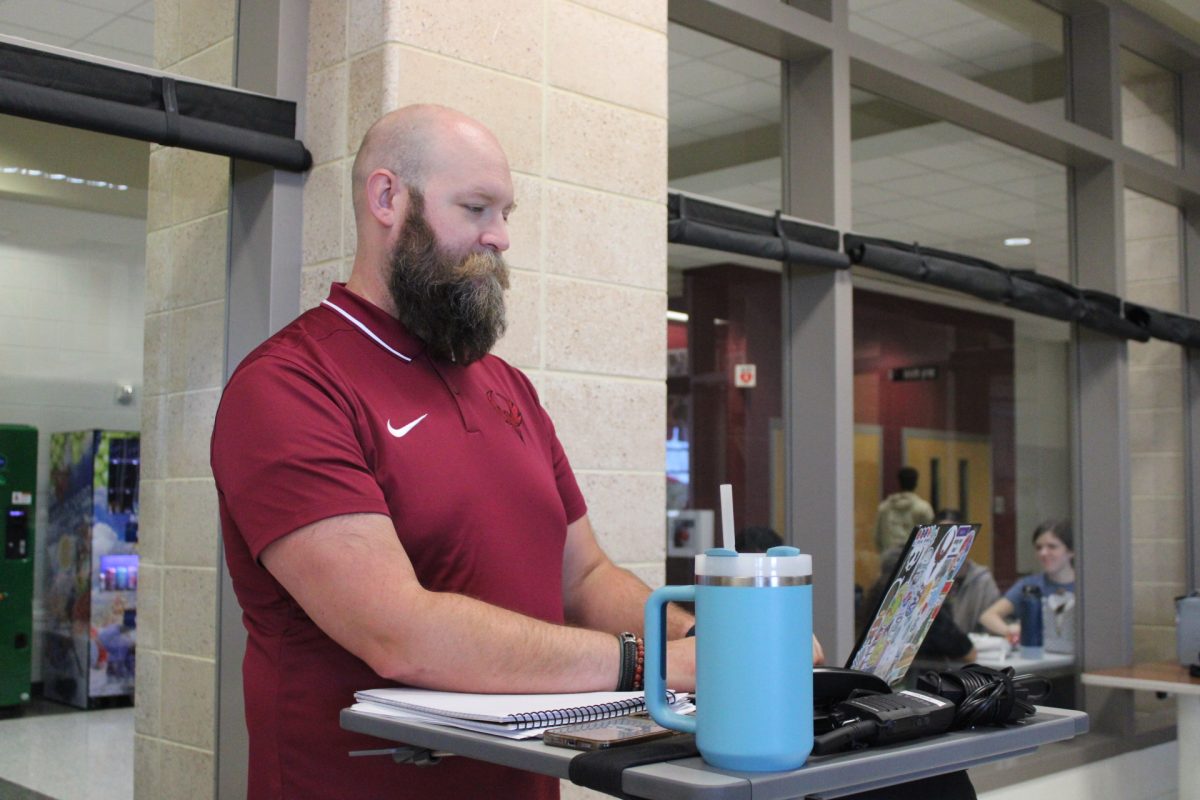

Let’s pose a simple question: how many of your classrooms have recycling bins? Five? Seven? When asking myself, I can only count one—and when asking my teachers and classmates, they report that science classrooms have the most dedicated recycling bins. “Considering I spend the majority of my time around science classrooms, I can say that we have the ‘most,’ as each classroom has at least one,” biology teacher Everette Callaway said.

The head custodian at Rock Ridge, Delfina Amaya, said that if teachers lacked a recycling bin in their classrooms, they could ask her or other custodians to provide them. However, many teachers claim that they were completely unaware of this amenity, and their inaction can possibly be attributed to the transition from online schooling to full in-person. “Before the pandemic, I had a large recycling bin,” world history teacher Katharina Felts-Wonders said. “When we came back, I didn’t have one of those boxes in my room anymore. I didn’t think it was something I had to ask for.” Felts-Wonders felt relatively overworked and busy with helping her students adjust, which could help explain why her and many other staff hadn’t marked recycling high on their priority list. “When we came back last year for hybrid learning, I would honestly say I was fully focused on my students … it was overwhelming.”

In comparison to multiple types of recycling bins, universal types of recycling fosters inherently unethical mixed recycling methods. Amaya has recognized this issue for years, and voiced her experience with Rock Ridge’s recycling system. “When Rock Ridge first opened, we were a lot more organized and we recycled properly, but now it’s completely out of my control,” Amaya said. “The problem arises from mixed waste management—it’s near impossible for us custodians to separate trash and recycling.” Despite these difficulties, the custodians still see some hope for a better recycling system, and want to avoid mixing trash with recycling. “We can fix this issue if all staff, students, and custodians put in more conscious effort to spread awareness,” Amaya said. “Our goal is to put waste in the proper bins.”

While this should be a prioritized and continuously supported effort, we must keep in mind that mixed recycling alleviates the confusion associated with the multitudes of recycling procedures. The temporary institutionalization of universal recycling bins can still prove beneficial to the student body, especially in this awkward transition period from online to in-person education.

So, after having done informal assessments of students and staff about their opinions on the school’s recycling system, one is left wondering: why has this issue not been addressed much earlier? The reality of our inquiry is that it has—and the efforts put forth proved to be much too cumbersome for the few people dedicated to finding a solution. Michael Clear, chemistry teacher and sponsor of the Environmental Club, recalls the history of Rock Ridge recycling as rather chaotic and hard to improve.

“As of a few years ago, we did not have a program set in place for classroom or cafeteria recycling,” Clear said. “During that time frame, the Environmental Club pitched in to help out by collecting empty water bottles during lunch hours.” They went on to take these bottles to a local recycling location directly, additionally collecting recycling from blue bins in classrooms, which was engaged during Rock Block. However, these efforts have been subdued over the years, and the cause can be attributed to a dwindling Environmental Club member count, and subsequent overwork of dedicated members. “It is a ton of work for the members,” Clear said. “We have not been able to do anything this year as we do not have as many active members as we once had.”

This apparent crisis is still under the radar and rarely talked about—and while it isn’t the administration’s highest priority, there are still things students and staff can do to help. Some methods involve establishing good recycling habits, such as spreading awareness and being cognizant of what you throw away; however, if you find yourself with free time or have the passion to put in active effort, rest assured that the help is not inconsequential. Sure, the ideal future would be a more sophisticated recycling system; but the first step we need to take to get there starts with recycling anything at all. Students should always be cognizant of placing trash in the correct bins–and if teachers are still missing these bins, let it be known that acquiring one is an email away. It is extremely important to understand that our ability to find a solution to this problem is predicated upon our individual effort as average members of society.

If you still find yourself lost on how to help, there are plenty of ways to start: contact our head custodian, Delfina Amaya, and help allocate dedicated recycling bins; present ideas to administrators and pose important questions, which can be done during school board meetings; or simply let a friend or peer know about the problem to spread awareness. Regardless of what approach you may take on this topic, if at all, it is clear that we must highlight the necessity of recycling system revisions. Furthermore, if we are to directly support any sort of revisions at all, we must also recognize an incessant Achilees heel within community problem solving: apathy.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

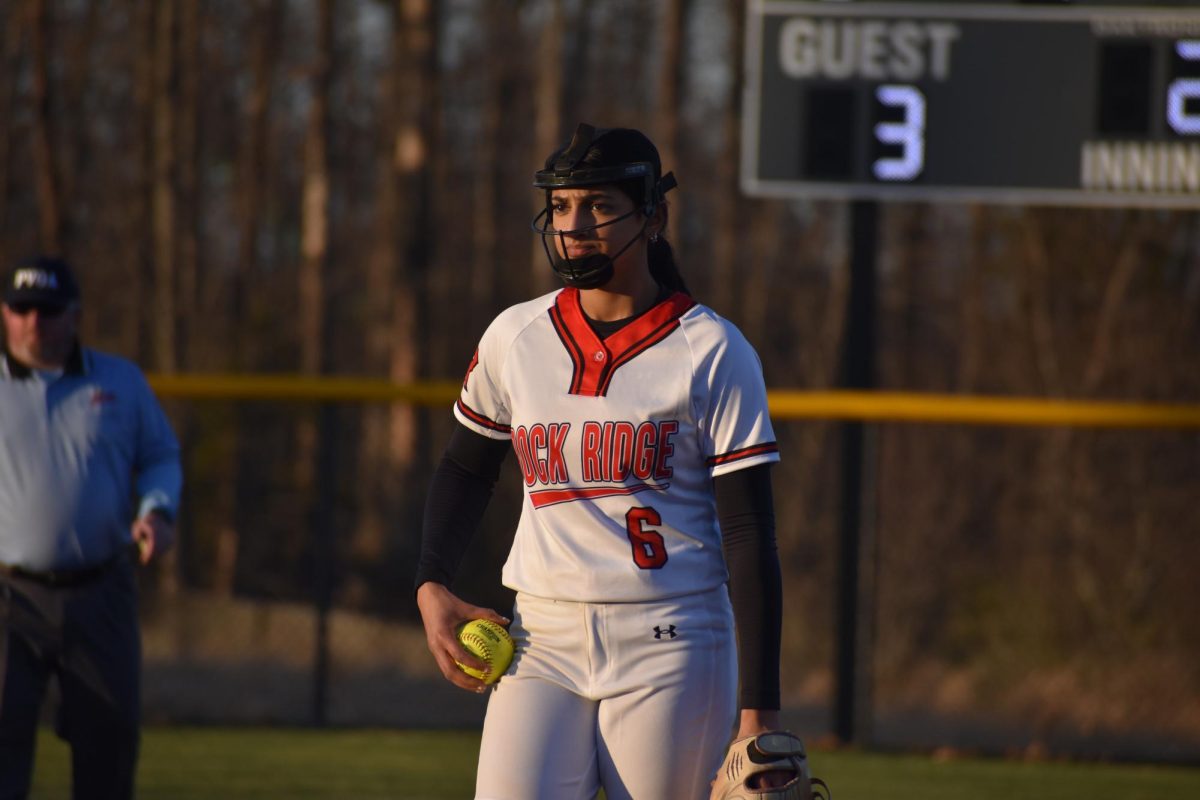

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)