Phoenix Immigrants: Their Lives, Struggles, and Experiences

Newly immigrated students struggle to navigate a new society and culture while trying to manage their school and social life. However, with help from school educators and county advocates, student immigrants are able to push through these challenges and find success.

A map in EL teacher Margareta Cernev’s room shows the names and countries of origin, written on the red phoenixes, of her current EL students. Above the map, the names and countries of origin of Cernev’s previous students, who have graduated from high school, are displayed on gray phoenixes.

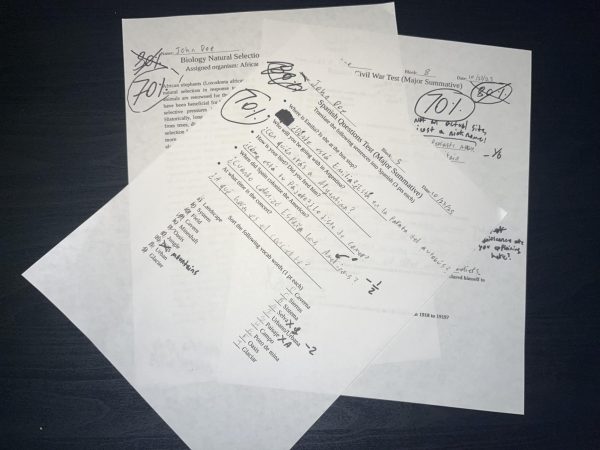

Sophomore Carlos Fuenmayor sits at his desk in his Spanish class, using his Chromebook to do research for a project. Fuenmayor immigrated to the United States from Venezuela. “It’s totally different here,” Fuenmayor said. “Here, we use cellphones in class, while in Venezuela, it’s prohibited. Additionally, people in Venezuela have a specific class in which we use computers and other types of technology, which is different from here, because we use [technology] all the time, in all classes, to do our assignments.”

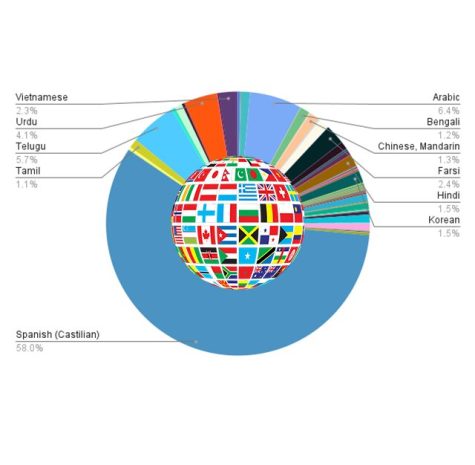

In Loudoun County Public Schools, around 18.8% (15, 943) students are enrolled in the EL (English Learner) program. About 105 of those students are members of the Rock Ridge community. County-wide, these immigrants represent over 110 languages, and they encounter various challenges such as language barriers and cultural differences. However, many support systems exist in the LCPS community to help these immigrants make an impact in their communities and find academic success.

Cultural Changes and Acculturation Challenges

Language barriers are just one of the many challenges that immigrants around the country experience during acculturation—the process of adjusting to a different culture. Some immigrants may have an easier time adjusting to foreign cultures if their native culture is similar to the new environment they’re acclimating to. For others, however, customs and norms that seem obvious and normal to American-born students might be an unusual experience for some immigrant students.

Fuenmayor noted the increased diversity of people and culture in the U.S. compared to Venezuela. “[In the U.S.], there’s different races and types of people, but [in Venezuela], I only saw people who lived in the same city as me,” Fuenmayor said. “Here, I can see many types of culture, which is very good, since I’ve learned about other countries.”

Junior Zakaria Mejjali, who immigrated to the U.S. in 2021, didn’t have a difficult time adjusting to life in the United States. He attributes this to the cultural similarity between the U.S. and Morocco, his home country. “Morocco has probably the same culture as America,” Mejjali said. “We listen to American singers, we wear the same clothes, so it wasn’t so hard for me.”

Junior Mai Dorgham remembered the feeling of surprise she experienced when she arrived in the U.S. from Egypt in July 2020 and saw her new house. “It shocked me,” Dorgham said. “In Egypt, the houses are way different; they are all buildings and apartments, so the only time I’ve seen a house like [the one I now have] was in movies.”

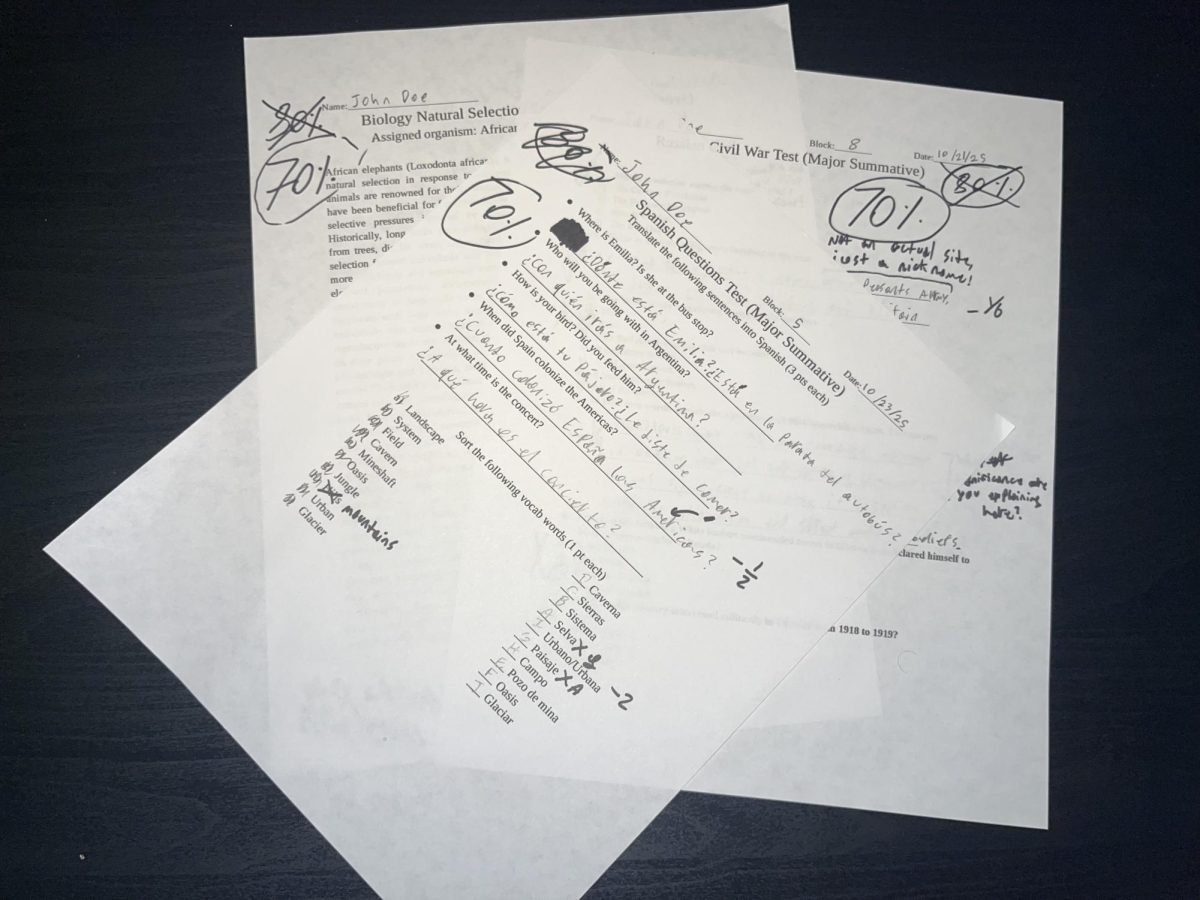

EL teacher Margareta Cernev cited the requirement to fulfill rigorous graduation standards as a challenge that her students face. “Everybody wants to graduate from high school and obtain the credentials that every student strives for,” Cernev said. “So, for the EL students, this is a double challenge, because on top of learning the language, they need to continue learning the concepts and to prove that they have knowledge of those concepts in a [totally] new language for them.”

Even though Dorgham spoke English before coming to the United States from Egypt, she had trouble keeping up with the speed of the language, especially during online classes last school year. “In my classes, I would have to record [the lessons] sometimes and listen to them again, because I didn’t know how to understand people who were speaking English fast,” Dorgham said.

Acculturation and language barriers aren’t the only challenges that immigrants face. Racism and xenophobia shun student immigrants out of school communities and make them feel unwelcome and unwanted. When freshman Julia Choi immigrated to the U.S. from South Korea and moved to North Carolina, she recalled that “most of [her] teachers were racist.” However, Choi has found the Rock Ridge community to be “more nice” and accepting of different cultures and immigrants.

Mejjali compared his experiences with acceptance in the school community with other immigrants’ experiences. “It was easy for me; the people accepted me quickly,” Mejjali said. “But I can see for some other immigrants that they seem confused, they sit alone.”

Support Systems

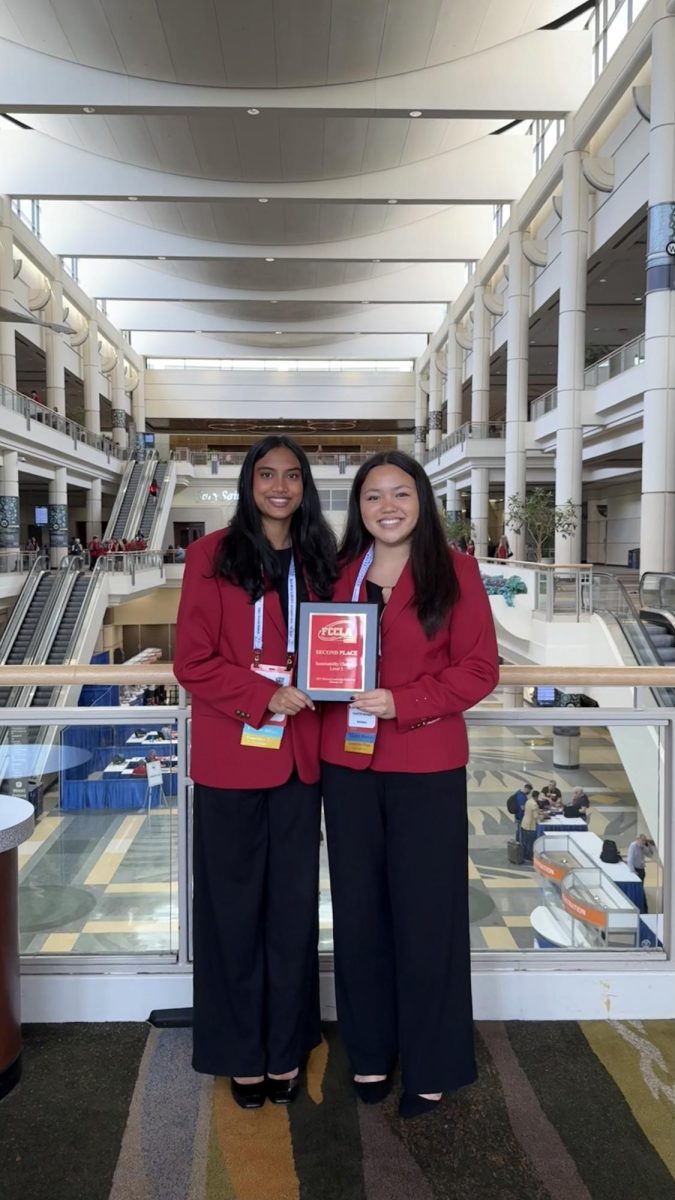

To help with these challenges, student immigrants receive support from both in-school and county systems. “There are programs in the school that help people from other countries, that speak different languages and are from different cultures, to motivate us to achieve higher things in school,” Fuenmayor said.

Counselor Katie Doppelheuer spent a part of her career assisting student immigrants enrolled in the EL program to overcome various obstacles that they face integrating into a new country. “I think part of the [challenge that they face] is acculturation, and just feeling like ‘Hey, I’m out of place here and I don’t really know what to do or where to go for certain things,’” Doppelheuer said.

One such system that helps guide EL families is the Family and Community Engagement team in the LCPS Division of English Learners. FACE is a team that works at the county level to help immigrant families that have children in the EL program. “A lot of [FACE’s] role is to create opportunities for English Learner families to have access to information, resources, and opportunities for them to hear directly from the division, and also support staff at the school base level who are wanting to engage with the English Learner division,” FACE Coordinator Veronica Cuadrado Hart said. “It’s a two-fold approach.”

FACE also helps English Learner immigrant families with establishing effective forms of communication with schools. “One of the simplest ways of helping families is just advocating for the fact that they may need verbal interpretation,” Cuadrado Hart said. “There’s so many different modes of communication that the LCPS staff use to communicate with families including emails, phone applications, [and] phone calls, so it’s important to provide information for [EL families] so that they can feel empowered to reach out to language assistant services.”

At the school level, the EL department works closely with the counseling department to help EL students who have recently immigrated to the U.S. to acclimate and adjust to their new school. “The EL department and the counselors work together to find which courses, in addition to the credits that they already have [from their home country], are necessary for the student to move on to pursue their high school graduation,” Cernev said.

Mejjali attributes his success in school to the hard work and dedication from his teachers and counselors. “They give me 100% of their help,” Mejjali said. “If they weren’t here, then I wasn’t going to go with my studies and I was going to quit at the beginning of the year. They’re watching my back; if I do something wrong, they catch me.”

These various support systems for EL students help them to excel academically. Data from the Virginia Department of Education shows that in Loudoun County, 59.1% of EL students acquire Standard or other types of diplomas, and 26.4% graduate with an Advanced Studies diploma. At Rock Ridge, 45.5% of EL students acquire an Advanced Studies diploma, and 54.5% graduate with a Standard or other type of diploma. Additionally, data from the 2018-2019 school year shows that out of the 29 EL students who graduated with a diploma at Rock Ridge, 22 went on to enroll in an Institution of Higher Education (IHE).

Cultural Impact and Immigrant Goals

These support systems help student immigrants look beyond high school and towards career goals. “I want to go to university,” Choi said. “Anywhere medical.”

Immigrant students and their families also have a broad cultural impact on their communities. “The wealth of cultures that we have at Rock Ridge definitely makes us richer,” Cernev said. “[Rock Ridge] students want to come together to show that there is value in all different cultures in the world, and definitely those cultures make our school community so much richer, so much [more] diversified, and so much more understanding and accepting.”

Immigrants from all over the world bring their vibrant cultures and languages to the Rock Ridge community. “We have many clubs that are culturally oriented,” Cernev said. “We have the Bhangra club, we have a new Egyptian club this year, [and] we have the International club.”

Cuadrado Hart believes that immigrants help build communities through their unique ideas and cultures. “Their language, the way they communicate, their traditions, their stories; truly, in every single way, [immigrants] are a benefit to our community,” Cuadrado Hart said. “The word ‘immigrant’ is synonymous with strength.”

“I came [to the U.S.] with only my parents and my sister and we had to start from zero,” Fuenmayor said. “But little by little, with hard work, we’ve been growing, and we’re going for more.”

*The interview with Carlos Fuenmayor was conducted in Spanish. All responses from him were translated into English by the reporter.

Rohan Iyer is senior and a third-year member of The Blaze. A passionate writer and reader, Rohan loves writing and editing articles for The Blaze, and he thoroughly enjoys helping design the newsmagazines...

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

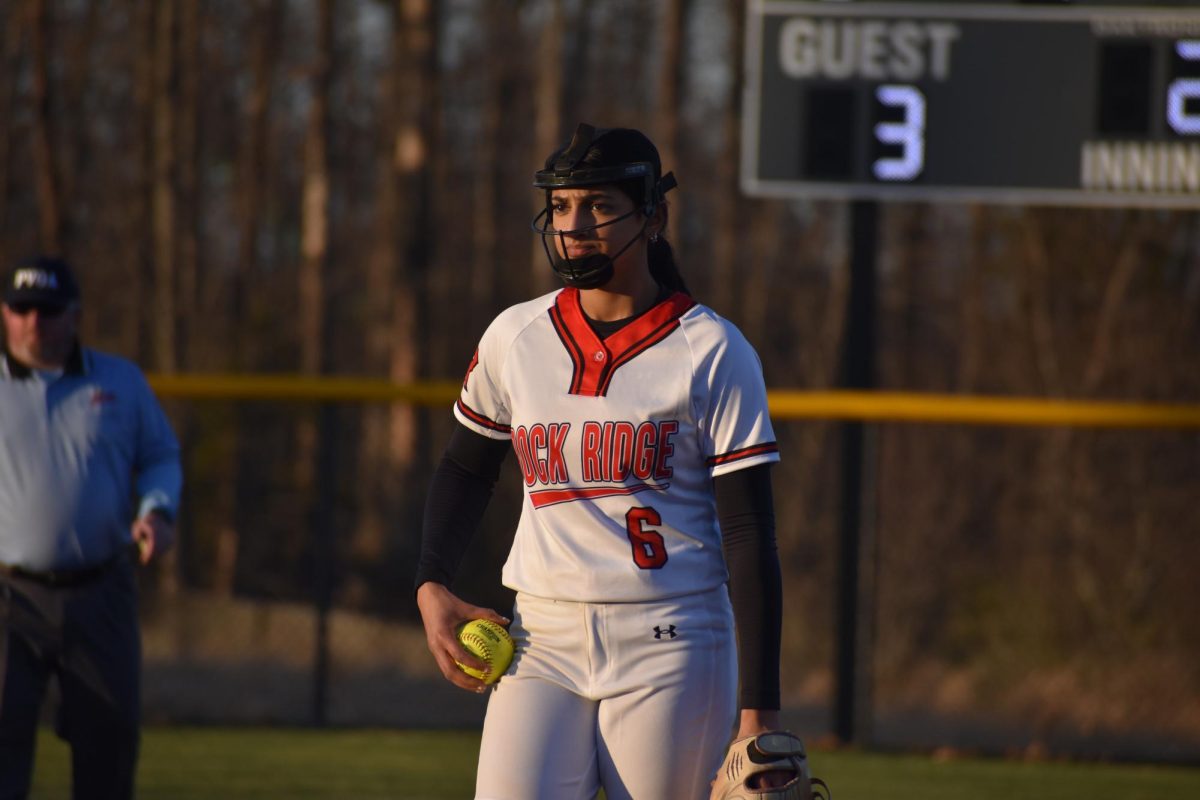

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)