The Silent Warnings of a Dying Island: Puerto Rican Statehood

It has been two years since the last referendum on Puerto Rico’s political status. Why has progress stalled?

Along many roads in Puerto Rico, there are graffiti messages concerning the politics of the island. The most commonly seen are “votar pa que” and “tu voto perpetoa la colonia,” which means “vote for what” and “your vote perpetuates the colony.”

January 19, 2023

I remember when Hurricane Fiona made landfall in Puerto Rico on Sept. 18, 2022. There was already an island-wide power outage, and flooding broke down roads in the mountains. A few hours in, I had already called it “Mariacita,” and I was terrified for the people caught within the storm. But Fiona was not like María back in 2017, whose rage encaptured the zemi of weather Guabancex; Fiona was just Fiona. Hours later, the hurricane passed the island and left damage reminiscent of the horrors that occurred in 2017. But that horror wasn’t just the torn houses, destroyed roads, and the terrified children drenched in dirty water: the horror included the US response.

In the article The Blaze published almost a year ago, “The Debate over Puerto Rican Statehood Hides Bigger Concerns,” I wrote about the imbalance of priorities concerning Puerto Rico, making the point that the debate over statehood wasn’t addressing the right problem. However, I must make some clarifications regarding the issue. Puerto Ricans are, like any American citizen, subject to follow federal laws, but Puerto Rican residents cannot vote in Congress or during presidential elections. This has ultimately led to intense arguments over which politicians would listen to them the best. This tension is intergenerational, dating back to the 20th century during the Puerto Rican independence movements. Most importantly, the debate over Puerto Rican statehood is deeply rooted in American imperialism and decolonization.

Puerto Rico’s secondary priority status was revealed once more after Fiona. Although President Joe Biden responded firmly to the disaster with relief funds, his response was slow. This reluctant view of the island has only been amplified by the seemingly unimportant votes made by Congress, which have not achieved further advancements on the political status of the island. Throughout the years, the locals have been asked the same question over and over: independence, or statehood?

Even the government itself finds difficulty in being able to spark a solution, as every discussion turns into an internet fight. By Nov. 18, governor Pedro Pierluisi included Puerto Rico’s status in his speech on the natural resources of the island. What ensued was a small dispute on Twitter that, ultimately, led to another stalemate.

However, Dec. 15 saw a mildly significant development unfold, the passing of a bill that would, once again, allow Puerto Ricans to decide their future status. Passing with a 233-191 vote, prominent political figures such as Republican Jennifer González-Colón and Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez advocated in support of the bill. The bill itself is seen as more of a compromise due to the fact that it fails to address the process of Puerto Rico’s status, especially if it were to become a state. The bill does reinforce the island’s stance on making their own decision, but the overall discussion of such is vague and only focuses on decolonization generally rather than specifically mentioning the deeply rooted impacts of American colonialism.

But the U.S. negligence of the island is a stark contrast to the past between them and Puerto Rico. After seizing the colony from Spain in 1898, the U.S. broke down Puerto Rico’s parliament and seized the main industry of the island, coffee, and replaced it with sugar companies from the U.S. This severely affected the Puerto Rican working class, as they had originally worked for the coffee industry, but as the American sugar companies bought more land, they were essentially kicked out. Over the years, there was a rise in unemployment.

The U.S. solution to this problem was Law 116, the forced sterilization of (mostly poor) Puerto Rican women, which was in effect from 1930 to the 1960s. In the end, 97 women were directly sterilized through tubal ligation and hysterectomy, and thousands underwent the same procedure even after the law was lifted. It is a startling period of women’s history in Puerto Rico, and acts as another reminder of how rooted American imperialism and colonialism is on the island.

Even after a century of the U.S. government oppressing Puerto Rican independence movements, forcing sterilization of unsuspecting Puerto Rican women, and the disruption of the economy that has left a scar on the island, the US still barely listens to those voices. In fact, they often go against them, such as the Supreme Court upholding a law that denies Supplemental Security Income benefits to disabled Puerto Ricans, despite them being US citizens on April 21 this year. The Puerto Rico referendums have not helped at all, the most recent a statehood majority win in November, 2020. Even though the majority for statehood won, the status of the island remains unchanged.

In fact, many of Puerto Rico’s issues have been unresolved or just barely enough to make any significant progress. The worst of this is seen through the tax exemption of living on the island, resulting in more Americans buying land, which has forced more Puerto Ricans to leave the island entirely, since they cannot afford to live there anymore. Now, the rest of the islanders have to wade around poor infrastructure, resulting in infrequent power outages, by using solar panels rather than relying on the grids supported by LUMA. Instead of the government, both the U.S. and Puerto Rico’s, helping to resolve many of the issues, the locals are forced to pick up the pieces themselves.

Although there is a growing group of supporters for independence, it is simply not enough to make actual progress in Puerto Rico. Even when new bills are introduced, this is a situation that might not be resolved for years to come, as people continue to divide themselves into three different groups: statehood, independence, or free associated state. Despite their disagreements, we can’t let these voices go unheard, not after the century of oppression, demonization, and colonization of Borinqueños.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

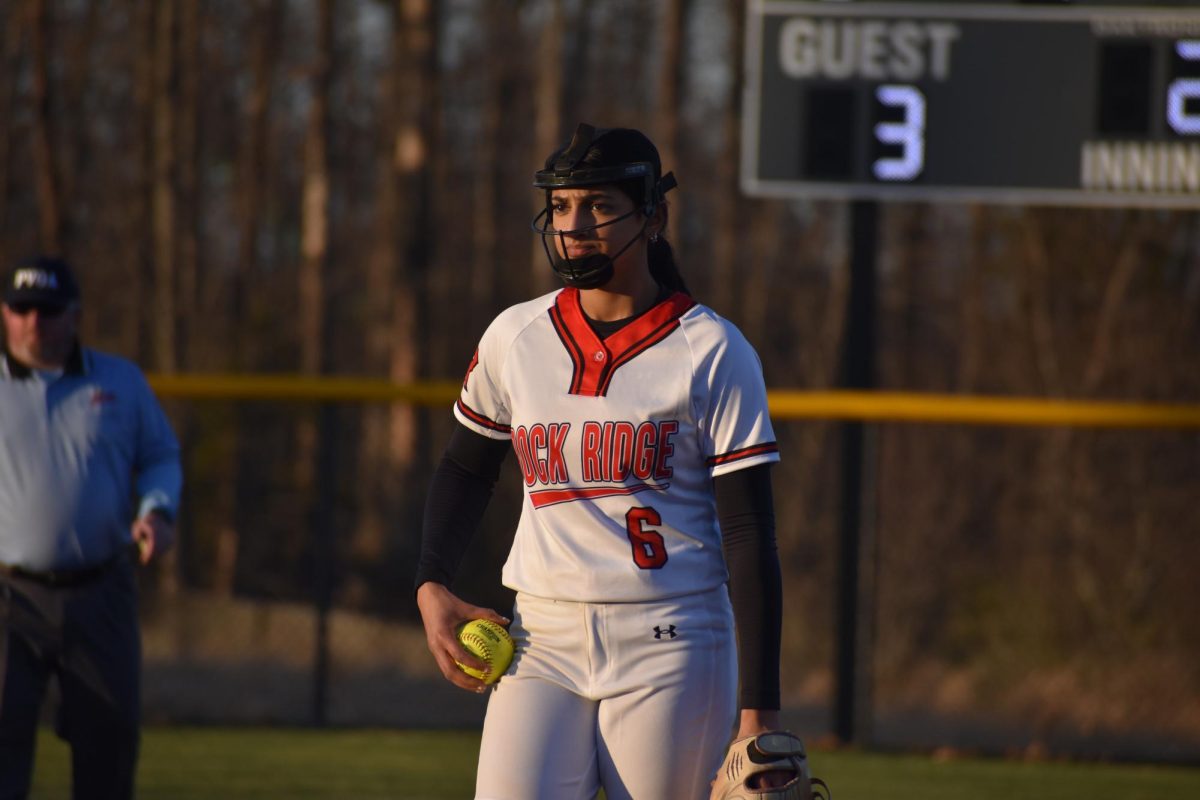

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)