There is no feeling more awkward than rejecting a donation plea from your local McDonald’s, or Hollister, or Macy’s… or seemingly anywhere nowadays. The reasons why people reject rounding up to the nearest dollar can range from wishing to save their pocket change to not trusting large corporations to properly donate the money.

People have a right to be suspicious, and while donations are typically well-meaning, there is a dark side. For example, the report by the Institute for Policy Studies delves into the practices of billionaire philanthropists and the implications of their charitable giving. It outlines how a significant portion of donations from individuals—over 41 cents of every dollar—end up in private foundations and donor-advised funds (DAFs), rather than active charities. This trend, termed “top-heavy philanthropy,” allows the ultra-wealthy to exert disproportionate influence over the nonprofit sector and public policy.

It also analyzes the Gates-Buffett Giving Pledge and proves case studies of giving pledgers, highlighting the disparity between pledge amounts and actual disbursements to working charities. It also examines the use of DAFs and private foundations by the ultra-wealthy as tax-advantage vehicles for charitable giving. The report criticizes DAFs for the lack of transparency and payout requirements, and it scrutinizes private foundations for practices such as funneling grants to DAFs to meet payout requirements and impact investments that serve the dual purpose of meeting payouts and reducing tax liability.

Furthermore, the report estimates the direct taxpayer subsidy for charitable giving to be $111 billion a year. It suggests that the legal framework governing philanthropy, established in 1969, is outdated and has been exploited by the wealth defense industry to avoid taxes and maintain control over assets. The report concludes by advocating for transparency and accountability in charitable giving to ensure that it contributes to the common good rather than serving as a tool for wealth preservation and tax avoidance.

So do businesses manipulate the system to the same benefit as certain philanthropists?

Businesses asking for donations at the register, often through “round-up” campaigns where customers can round up their purchase to the nearest dollar for charity, are engaging in a form of philanthropy. However, it’s different compared to the practices of billionaire philanthropists. When businesses ask for donations, they facilitate micro-donations that are then passed on to charitable organizations or causes. This method relies on the collective contributions of many customers to make an impact. It’s a way for businesses to engage in corporate social responsibility and for consumers to contribute to variable causes in a convenient manner.

It’s also a common misconception that businesses use customer donations at the register to reduce their own tax expenses. However, in reality, businesses can only claim deductions for their own charitable contributions, not for the donations collected from customers. The tax policy is signed to ensure that the entity making the charitable contribution receives the corresponding tax benefit. Or, in other words, the business cannot claim a tax deduction for customer donations, as the money does not come from the company’s funds.

But you can claim a deductible… kind of. Here’s how you do it.

Firstly, make sure to keep all your receipts that show you’ve made a donation. Then, at the end of the year, add all of the donations. For the deduction to be beneficial, the total of all itemized deductions, including the charitable contributions, would need to exceed the standard deduction. The standard deduction for a single person filing in 2024 is $14,600. In simple terms, a standard deduction is like a no-questions-asked discount on your taxes. The government says, “We’ll let you reduce your taxable income by this much, and you don’t need to show us any receipts.” An itemized deduction is like keeping all your receipts throughout the year for things like donations, email expenses, and mortgage interest. At the end of the year, if the added total is more than the standard deduction, you can use this larger amount to reduce your taxable income instead. Only about 9% of households claim itemized deductions and those that do tend to come from higher-income households. This means that while the option to deduct these donations exists, it is not commonly used. However, you can bunch together contributions by combining several years’ worth of donations into one year to surpass the standard deduction threshold and claim a larger deduction, but that again only applies to the minority of people that itemized deductions. Standard deductions are notably much easier, and the amount given isn’t ungenerous. Small donations, like rounding up your bill at the store, usually don’t add up to enough to beat the standard deduction. At least not for many, many years.

Overall, a donation is still a donation, and a majority of businesses are paired with reputable charities that use the given money to benefit the community and a variety of causes. While the tax benefits aren’t high, rounding up your $15.67 purchase to the next dollar may be a great way to make a small difference in someone’s life.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

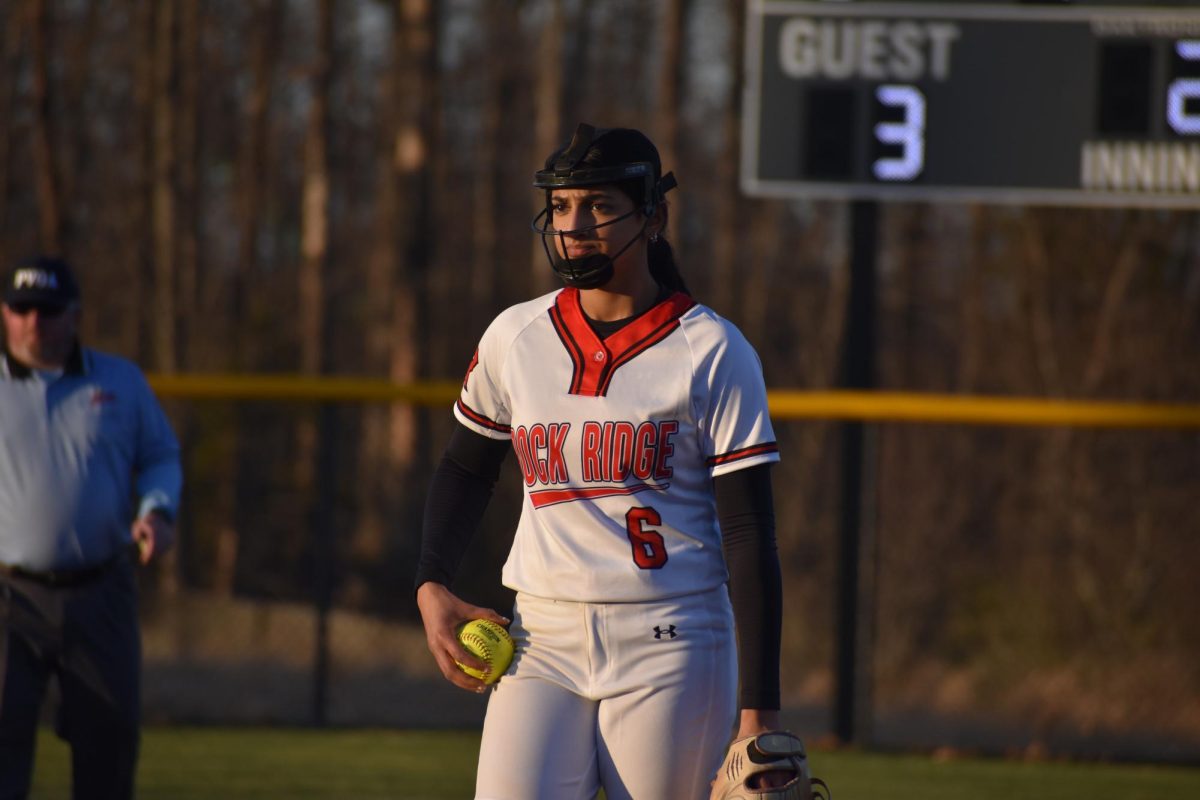

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)