Content Warning: This article contains mentions of violence and sexual abuse.

Two murders, one sensational trial — and “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story” still manages to miss the mark completely. Fresh off the exploitative success of “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,” director Ryan Murphy has returned with “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story,” a deeply questionable rehash of the infamous 1989 Menendez brothers murder case. Like all of Murphy’s true-crime adaptations, the series is sensationalist, gratuitous, and disturbingly cavalier in its treatment of real-life trauma. Once again, Murphy has proven that when it comes to exploiting human suffering for entertainment, nothing is off-limits.

The Menendez case was already a media circus, with lurid details of the brothers’ sexual abuse at the hands of their father clashing with accusations of greed-driven murder. But “Monsters” doesn’t attempt to add any nuance or insight. Instead, it plays like a horror show, twisting the brothers’ trauma into dramatized fodder for Netflix’s true-crime-hungry audience. Murphy and his co-creator Ian Brennan insist they approached the material with sensitivity, claiming they wanted to explore the issue of who is believed and who isn’t in cases of sexual abuse. Yet, this lofty rhetoric crumbles under the weight of a show that has no coherent perspective and indulges in grotesque fabrications — most notably, a wildly inappropriate scene implying incest between the brothers, a claim with no basis in fact.

This is Murphy’s modus operandi: present half-baked moral ambiguity under the guise of prestige TV, all while mining real people’s lives for drama. “Monsters” wants to have it both ways — it wants the gritty, raw appeal of a true-crime drama, but also the pulpy, Tarantino-esque thrill of watching rich boys with shotguns. The result? An incoherent mess. The tone hurtles wildly from gut-wrenching accounts of abuse to scenes soundtracked by upbeat 80s pop songs. In the sixth episode, “Don’t Dream It’s Over,” audiences are forced to sit through a graphic testimony about the brothers’ abuse one minute; the next, “Don’t Dream It’s Over” by Crowded House plays while they walk toward their parents’ murder. Murphy seems to think he’s making a smart, edgy commentary on trauma and power, but what he’s really doing is fueling the billion-dollar true-crime entertainment machine with reckless abandon.

The most glaring issue with “Monsters” is that it doesn’t know what kind of story it’s telling. Are Erik and Lyle Menendez tragic figures, pushed to commit an unthinkable crime after years of sexual abuse, or are they cold-blooded killers manipulating the narrative for sympathy? Murphy can’t seem to decide, and the brothers are reduced to grossly-depicted caricatures. Lyle, in particular, is shown as a devilish sociopath in one moment and a broken victim the next, with no effort to show whose perspective viewers are meant to trust. The result is a confusing, tone-deaf portrayal that does more harm than good in examining the complexities of abuse and violence.

Despite the show’s many flaws, the performances in “Monsters” are undeniably powerful. Nicholas Alexander Chavez and Cooper Koch bring a haunting vulnerability to their roles as Lyle and Erik Menendez, capturing the emotional turmoil beneath their characters’ surface bravado. Chavez, in particular, shines as Lyle, shifting between anger, fear, and desperation with startling intensity. Javier Bardem’s portrayal of the tyrannical José Menendez is chilling, while Chloë Sevigny gives a nuanced, tragic performance as Kitty. Even when the script falters, the cast manages to elevate the material, delivering moments of raw emotions that almost make viewers forget the show’s missteps.

However, even when “Monsters” attempts sincerity, it stumbles. A 29-minute monologue in which Erik recounts the sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of his father is shot in a single, excruciating take — a clear attempt at emotional depth. But this brief moment of raw storytelling is immediately undercut by the surrounding spectacle. The narrative is overwhelmed by fabricated details and sensationalism, leaving little room for any meaningful exploration of the abuse or the justice system’s failing.

The biggest problem? The Menendez brothers are still alive. They maintain their innocence and allege horrific abuse, and yet Murphy treats them like characters in one of his “American Horror Story” anthologies. Erik Menendez himself has condemned the show as “vile and appalling,” accusing Murphy of exploiting his and his brother’s trauma for profit. It’s a charge that’s hard to argue against when one considers Murphy’s history of producing true-crime spectacles without consulting the real people involved — a deplorable pattern of using trauma as content.

Cynically, Murphy’s approach makes sense. “Dahmer” drew massive viewership, so why not repeat the formula? After all, no amount of moral backlash has slowed Murphy down before. Netflix saw the numbers, ignored the complaints from victims’ families, and handed Murphy the keys to another true-crime goldmine, a goldmine–which includes “Dahmer”–that has made Netflix over $341 million. That’s the real tragedy — not just that Murphy continues to exploit these stories, but that audiences continue to reward him for it.

In the end, “Monsters” doesn’t offer any real insight into the Menendez brothers’ case or the societal issues the series supposedly tackles. Instead, it rehashes familiar themes, playing fast and loose with facts to keep viewers hooked. Murphy’s blend of trauma and entertainment is more than distasteful — it’s irresponsible. It’s not here to tell a meaningful story — it’s here to sell one. Murphy may call it entertainment, but there’s a fine line between intrigue and insult, and he crossed it a long time ago. The real mystery? Why we keep tuning in for more.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

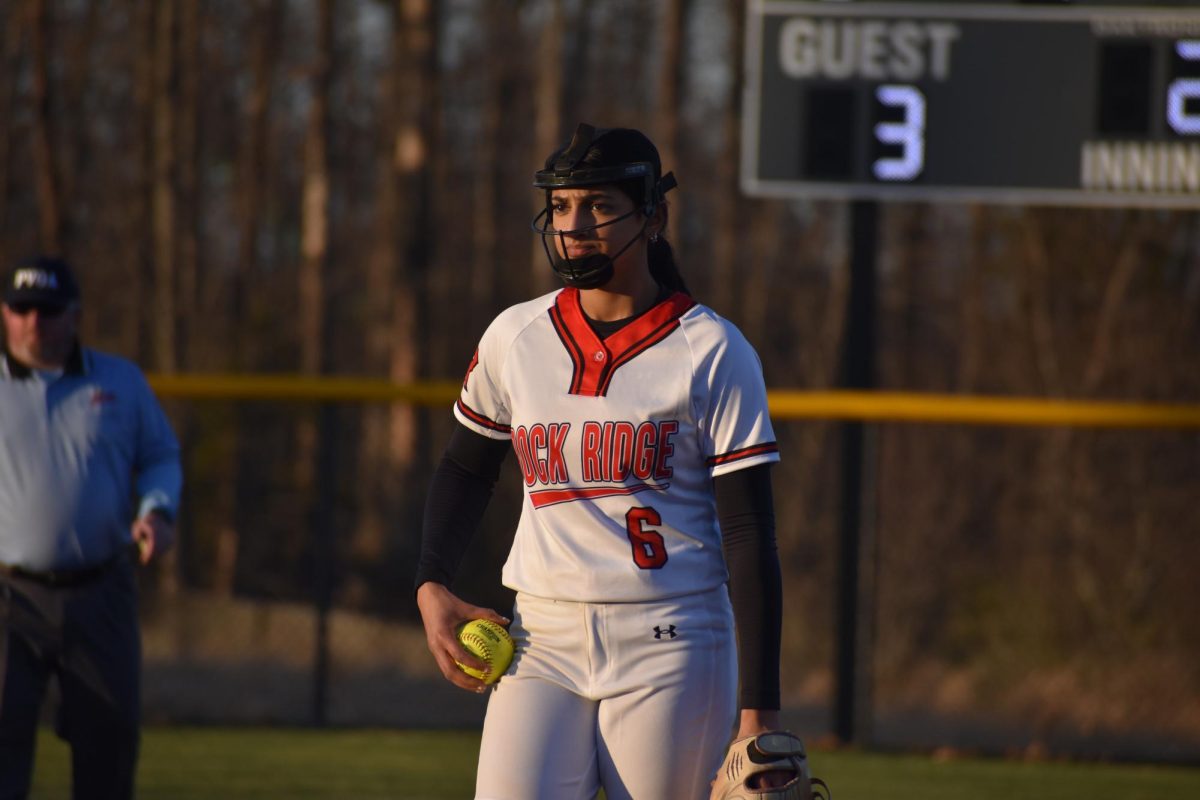

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)