When I was a sophomore, a senior in my journalism class achieved what felt, at the time, like an act of divine intervention: she got into Stanford early action. By mid-morning, the school was abuzz with the news. By lunchtime, her application had been deconstructed in forensic detail. “Was it her 4.7 GPA?” “Her 12 APs?” “Her leadership roles?”

We dissected her success as if it were a rare specimen under a microscope, an elusive formula we could recreate. We became coroners determining which strokes of brilliance kept it alive and which flaws might have killed it. What was meant to be a celebration became more of an autopsy.

I was a sophomore then. I’m a senior now — and this culture has only intensified. Rock Ridge, and a large majority of high schools in the country, are high-achieving pressure cookers where a 17-year-old’s worth isn’t measured in kindness, curiosity, or character, but in college acceptance rates — preferably in the single digits.

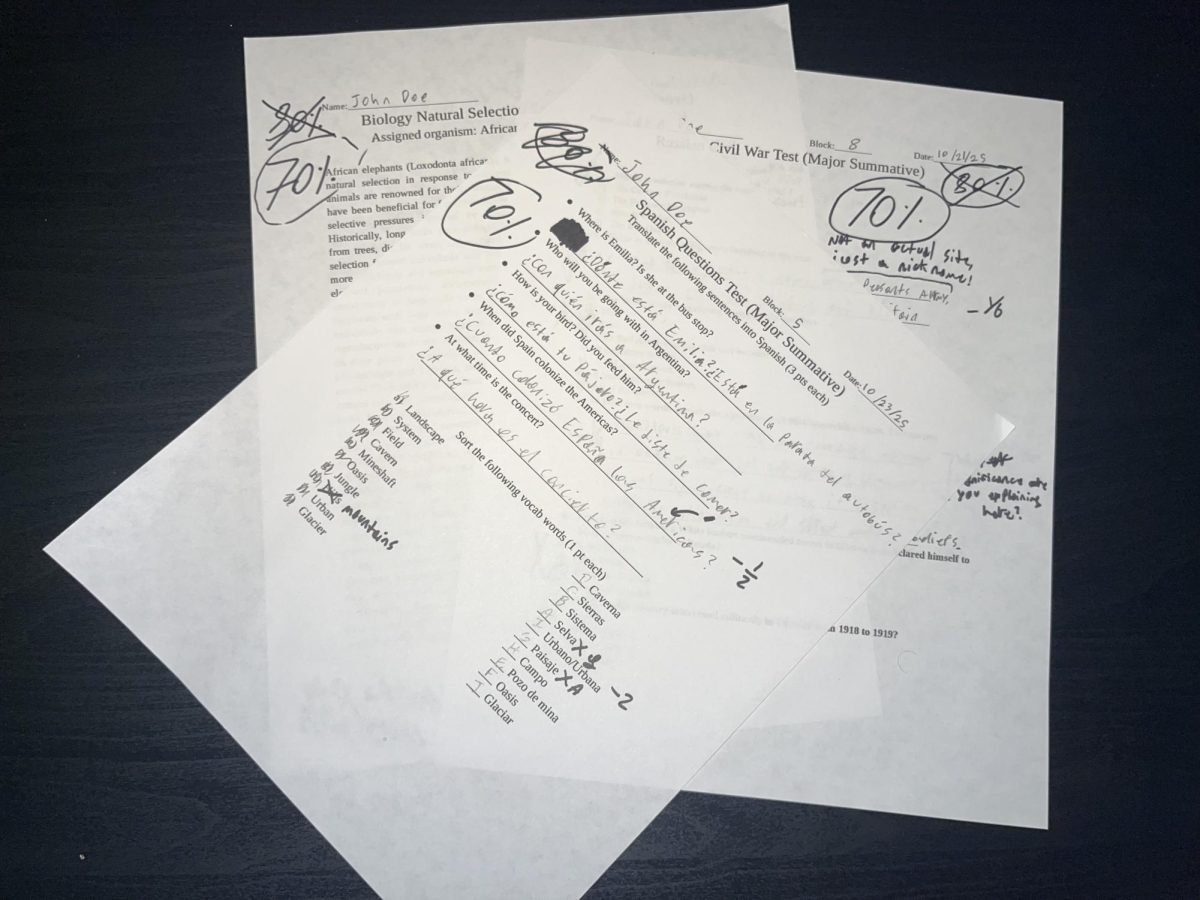

We all play the game. We know the rules: perfect grades, impeccable test scores, and at least three passion projects so unique they could pass as indie film plots. Forget simply excelling in school. Today, you need to have saved the whales, led a protest, and written a memoir by the time you blow 18 candles.

And soon, learning becomes incidental, and winning becomes the goal. But this mindset is nothing new. What is new is the fever pitch it’s reached. The college admissions process — what should be a relatively straightforward assessment of grades and potential — is instead an arms race fueled by anxiety, privilege, and the bizarre notion that a rejection from an Ivy League school is equivalent to a life sentence of mediocrity.

The numbers don’t help. In 2024, the average acceptance rate across Ivy League universities dropped to just 5.1 percent, a sharp decline from 8.9 percent in 2015, highlighting the skyrocketing competition for a spot at these elite schools. With these institutions boasting rejection rates north of 90 percent, students scramble to distinguish themselves. And admissions officers, in turn, are happy to fan the flames. Extracurriculars? Not enough. They need to be “authentic.” Leadership? Great, but it has to be “meaningful.” Community service? Sure, but it better be heartfelt — and documented on Instagram.

This cutthroat culture is especially potent at schools like ours — in a highly competitive region, with magnet schools like the Academies of Loudoun and the Thomas Jefferson High School of Science and Technology pumping out Harvard, Princeton, and MIT admits every year. It’s a toxic system — and we’re all complicit.

But let’s not forget who set this maze. Colleges themselves laid their traps and set the rules.

Take the rise of the Common Application in the early 2000s, which made it easier than ever to apply to multiple schools. Since its expansion, colleges experienced a 10 percent jump in the number of applications for admission. This surge has led to a decrease in acceptance rates, with schools like Stanford admitting as few as 3.9 percent of applicants. The Common App was great for access, sure, but it also flooded admissions offices with applicants, forcing them to tighten their standards and invent new ways to rank students. Enter the era of holistic admissions, where test scores and grades weren’t enough. You needed “grit.” You needed “leadership.” You needed to turn yourself into a brand by age 15.

Today, colleges market themselves like luxury goods. They hire consultants to attract applicants they know they’ll reject, because the fewer students they accept, the more prestigious they’ll seem — it’s Kafkaesque.

And, yet, we buy into it. The promise of prestige, the allure of exclusivity: it’s almost intoxicating.

But at what cost?

The toll on students is enormous. Sleep deprivation, anxiety, burnout — these are not only the effects of academic rigor; they’re the norm. Students drop activities they once loved because they’re not “application-worthy” or they spend more time calculating their weighted GPA than actually studying. As for me? I can’t count the number of hours I’ve spent obsessing over whether my extracurriculars sound impressive enough (Does “Policy Advocate” sound better than “Board Member?” “Writing Mentor” instead of “Writing Tutor?”).

And it’s not just the students. Parents, too, are caught in this vicious cycle. They spend thousands on SAT tutors and college consultants, ferrying their kids from one résumé-padding activity to another. It’s exhausting, unsustainable, and, honestly, absurd.

But the worst part? None of it guarantees anything.

A perfect SAT score, a spotless transcript, or even a Pulitzer-worthy personal statement can still be met with rejection. After all, when schools like Harvard receive over 56,000 applications and reject more than 54,000, the odds are stacked against everyone. The process then becomes more about who fits into the arbitrary puzzle pieces admissions officers need that year — an oboe player, a squash champion, a future astronaut.

That’s the cruel irony: while students and parents exhaust themselves trying to craft the perfect application, the criteria for “perfection” shift with every admissions cycle. There’s the myth of the “spike” — a highly developed talent or passion that sets students apart. The idea is that depth in one area is more impressive than breadth across many. While this strategy can display genuine passion, it can also lead to students artificially creating interests they believe will appeal to admissions officers. This kind of performative authenticity is exhausting, and, ironically, transparent to seasoned admissions officers.

Some students, in a bid to outsmart the system, apply as humanities majors, like Comparative Literature or Russian Studies, despite a passion for STEM subjects, like Mechanical Engineering or Computer Science. The belief is that it’s easier to gain admission in less saturated fields, only to switch majors once admitted. Not only does this undermine the integrity of the admissions process, but it also forces students to contort themselves into shapes they don’t recognize, all for a coveted acceptance letter.

So, how do we break the spell?

We could start by asking colleges to rethink their admissions processes. Scrap the charade of “holistic review” and focus on actual academic achievement. Stop rewarding schools for rejection rates and start valuing them for their teaching.

But change doesn’t just lie with these elite institutions. It lies with us. We need to stop glorifying the Ivy League as the pinnacle of success. Stop equating a college acceptance letter with self-worth. Stop letting this system define who we are.

We don’t need to be coroners, analyzing the grisly details of every achievement as if success is something lifeless to be picked apart. Instead, we need to be sculptors, intent on shaping the future with purpose, passion, and a little mess along the way.

At the end of the day, your value isn’t determined by the university name on your diploma. It’s determined by the risks you take, the questions you ask, and the impact you make.

And if that sounds like something you’d find on a college brochure, maybe it’s time to start believing it — and start living it.

Ria Athreya • Jan 22, 2025 at 2:52 pm

omg this story ate