Loudoun County Public Schools (LCPS) is no stranger to controversy — nor to the consequences of enforcing Title IX ineffectively in the past. Mishandled sexual assault cases have placed the district under a harsh national spotlight, turning it into a case study of what happens when accountability falls short. The law is clear in its intent: protect students, ensure equity, and address harassment. But in practice, enforcement is only as strong as the system behind it.

LCPS, like all districts, is required to comply with Title IX, ensuring equal opportunities in athletics, maintaining gender equity in academics, and, perhaps most crucially, addressing sexual harassment and assault.

And as LCPS works to strengthen its Title IX policies this year, one thing is clear: knowing Title IX exists is not enough. Students and staff need access, clarity, and protection that feels real — not just theoretical. To this end, the Title IX team at the county-level intends to provide additional, concentrated training for teachers and administrators at each school this year to remind them of their responsibilities and emphasize the importance of the law.

The Evolution of Title IX: Beyond the Gymnasium

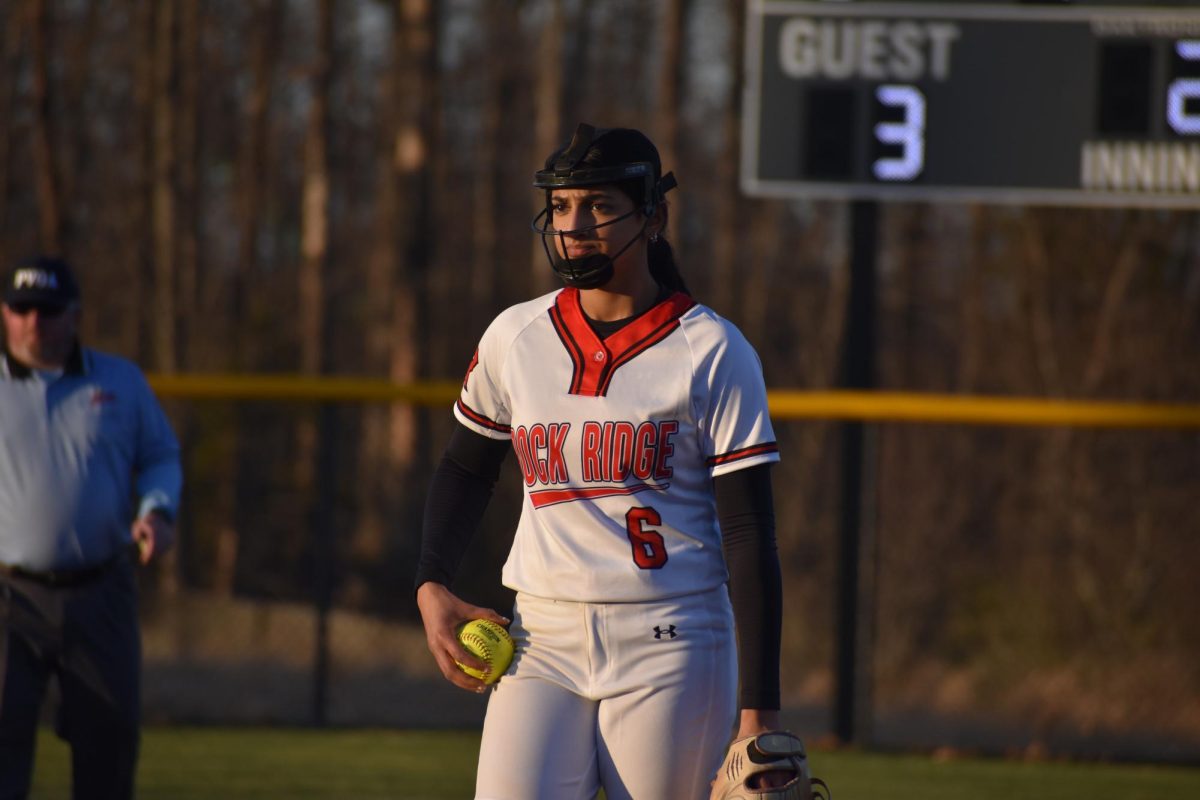

Ask the average person about Title IX, and they’ll likely mention sports. And they wouldn’t be wrong: Title IX has revolutionized women’s athletics, forever changing high school and collegiate sports by ensuring female athletes receive equal funding, facilities, and opportunities. But Title IX’s original intent went far beyond the locker room. It was, and remains, a sweeping anti-discrimination law aimed at securing gender equity across all aspects of education.

English and Women & Gender Studies teacher Jessica Berg, who is Rock Ridge’s Title IX Coordinator, emphasized the broader significance of the law. “It’s massively important because when it first became a law, a lot of people thought it was about sports,” Berg said. “And whereas yes, that did become an aspect of it — equal representation in men’s and women’s sports in any federally funded school institution — the biggest thing is access to education, equitable access. I went to UVA, and women weren’t [even] allowed to go to college until the ‘70s. That was such an important moment to create that opportunity initiative and make it law so that these institutions would start to allow women.”

This historic shift paved the way for a new era of gender equity in education. But today, the most pressing issues surrounding Title IX are not about who gets to play on the varsity soccer team. They’re about whether students feel safe in the classroom.

Originally adopted in 1999 as Policy 8-6, LCPS’s Title IX policy has undergone multiple revisions, with the most recent update March 2022 aimed at strengthening and protections and compliance measures. The revised Policy 8035 clarifies reporting procedures, mandates comprehensive training, and reinforces the district’s responsibility to investigate and address sex-based discrimination. “The whole role of Title IX is to reduce and eliminate barriers caused by sex discrimination and sexual harassment,” LCPS Title IX Coordinator Christopher Moy said. “Students may not be able to go to classes. It may be impacting their ability to learn.”

However, the existence of Title IX doesn’t ensure its daily implementation and enforcement. For many students, the reality of reporting harassment is far more complicated than the law suggests.

The Bureaucratic Maze of Sexual Harassment Cases

Title IX requires that schools investigate allegations of sexual harassment that, according to the Title IX guidelines, are “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it denies a person equal access to education.” In theory, this provides a clear framework for addressing sexual misconduct. In practice, however, Title IX enforcement often falls into a bureaucratic labyrinth, leaving students to navigate confusing reporting systems while schools grapple with the complexities of compliance and transparency.

Even with Title IX guidelines in place, their effectiveness depends on how well they’re understood and implemented. “We just pretty much did a 15-to-20-minute training session [for teachers],” Berg said. “‘This is what Title IX is, and this is your role as a teacher.’ We’re mandated reporters, and a lot of it was just running through scenarios. If you hear a student talking about [sex-based discrimination or harassment]; as English teachers, if you get something in writing; if a student comes to you, this is what you do. And that was kind of the goal: making it a clear, transparent reporting system.”

The training this year marked one of the first efforts to go beyond the basics, reinforcing educators’ responsibilities and ensuring that they understood the weight of their role. However, for many, it was a rare reminder of obligations that had never been thoroughly addressed before.

“I don’t think [educators] understand their responsibility at all,” Berg said of faculty at LCPS. “That is by no means the fault of teachers, and that is why I wrote the Title IX Education Initiative for our county. The information — it’s not readily available. Most people don’t really even know what Title IX is, what it covers, and most students don’t know that they have rights sitting in this school right now under Title IX. And so with anything, I always feel like that’s the first step if you want to create change: it’s the education.”

By equipping educators and students with a clear understanding of Title IX, the initiative aims to simplify what is often seen as a confusing and bureaucratic reporting process. When teachers recognize their role as mandated reporters and students understand their rights, it removes barriers to actions, taking a complex and opaque system and turning it into one that is accessible and responsive.

The Paper Trail: What Happens After a Report?

At LCPS, any faculty or staff member who witnesses or hears about an instance of sex-based discrimination is a mandated reporter, meaning they must pass the report along to the Title IX office. “We have a reporting system where all reports come into my office to review to determine: is this Title IX sexual harassment? And if it is Title IX sexual harassment, then those cases are handled by my office,” Moy said.

Despite the clear mandate for faculty to report instances of sex-based discrimination, the scale of the issue often goes unnoticed. Many educators are unaware of just how frequently these cases arise — or how many reports never make it to a formal investigation. “The Title IX [team], when they came to do our training, asked our staff, ‘How many Title IX investigations do you think occurred in the county this year?’ And it was over 300,” Berg said. “And those were [the] ones that met the criteria for investigations; the number of complaints was more than that. And as I always tell [the] Women & Gender Studies students, sexual violence is the most underreported violent crime because people don’t know [and cannot confirm] where [and] when [they happen].”

Then comes the part that students may find unnerving: transparency. While confidentiality is valued, Title IX regulations require that the accused be made aware of the allegations and given access to the investigative findings. The process includes collecting statements, reviewing evidence, and ultimately determining whether the claim meets the Title IX standard for sexual harassment: behavior that is severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive.

But this transparency under Title IX is still a careful balancing act. “I can’t accept an anonymous complaint,” Moy said. “I mean, I get anonymous complaints, but I can’t do an investigation if somebody wants to remain anonymous.” While this ensures due process for both parties, it also means students must attach their names to complaints, a requirement that can deter some from coming forward.

Confidentiality, however, does not mean secrecy. “Once we complete an investigation and before we go to decision-making to determine whether there’s a violation or not, we are required to share with the parties everything that we’ve collected during our investigation,” Moy said. This includes transcripts of interviews, documentary evidence, and a full investigative report — all of which are shared with the involved parties for review.

The Gray Area: Off-Campus Incidents That Spill Into School

But what happens when an incident takes place off school grounds? The short answer: it depends.

“There are cases where, let’s say, something happens off campus, outside of school; maybe somebody’s at a party over the weekend, and they’re sexually assaulted,” Moy said. “Or somebody is exchanging nude pictures outside of school, and then, the following week, it comes into the school and people are spreading rumors, and the person that this happened to is now being harassed in school. That’s what I call an in-program effect.”

In those situations, LCPS cannot investigate the original incident, but it can intervene in the school-based retaliation that follows. “It just gets into this gray area, specifically with K-12 public schools because [the students] are minors,” Berg said. “A lot of this stuff might happen off school grounds, but it can still impact your access to education in school, so it still could be a Title IX issue. It could be a student at a different school, but it could still be a Title IX issue.”

While Title IX may not extend to incidents that occur outside of school, LCPS remains committed to addressing the ripple effects that impact students within its walls. By stepping in when harassment, retaliation, or hostile environments arise as a result of off-campus incidents, the Title IX office ensures that students can continue their education without fear or disruption.

What Students (and Parents) Need to Know

For many students, Title IX protections are theoretical until they become personal. When students experience discrimination or harassment, they often face a maze of policies and the possibility of retaliation.

To prevent any kind of retaliation from the accused, LCPS enforces no-contact directives, class schedule adjustments, or, in some cases, transfers to different schools. “We do work with the individual,” Moy said. “The supportive measures we provide ensure educational access and a safe and supportive educational environment.”

The Title IX team at LCPS intends to clarify potential doubts at the “Rise To” Women’s Summit on March 22, hoping to give students a clearer path to reporting misconduct — one that doesn’t require filtering concerns through a teacher first.

This kind of direct-access reporting is critical, especially in cases where the alleged perpetrator is a teacher, coach, or administrator. “Something that’s different for a staff member [who is] accused of [violating Title IX policies], [if] we find that there is support to that allegation, that staff member may be put on administrative leave,” Moy said. “Now, that’s [not] necessarily happening every time, but it is something we can do as part of the Title IX process.”

The Politics of Protection

Title IX is not a static law. It has been rewritten, expanded, and challenged repeatedly since its passage. Under the Biden administration, proposed 2024 regulations aimed to expand protections, including restoring protections for LGBTQ+ students and strengthening reporting requirements. However, legal challenges have stalled their implementation. The Trump administration has also begun rolling back protections expanded during the Biden administration, particularly those related to LGBTQ+ students and victims of sexual misconduct.

But Moy confirmed that this should not have a significant impact for LCPS. “Nothing is new for us,” he said. “We never implemented the 2024 regulations because there was a federal injunction against our state in implementing those, so the regulations have stayed consistent with us and what we are doing [currently].”

For all the policies and procedures in place, Title IX enforcement in LCPS and across the country ultimately boils down to whether students, teachers, and administrators actually understand how it works.

That’s why LCPS is taking its message to students directly. “Our next step and why the Title IX team is coming to the [‘Rise To’] summit is to get students aware that [they] have rights, and [they] don’t even have to go through a teacher to report,” Berg said. “Here’s a form, and you can take it directly up the chain through Title IX, because not everybody would necessarily feel comfortable coming to a teacher with certain issues.”

Berg sees LCPS as having an opportunity to lead. “I think [effective education] is really going to help us stay on par, if not move ahead, [and] be proactive with a lot of these issues and educate our students on their rights,” she said. “I think we can really be a leader in this issue and set the tone for other school systems, not just in Northern Virginia, but beyond.”

One place this important education is taking place is in the Women & Gender Studies elective taught by Berg. “People may not know about their rights because they aren’t taught them,” Women & Gender Studies student senior Drithi Pinnamaneni said. “I learned about Title IX from Ms. Berg. We have the right to not be around someone at school if they have sexually harassed you, meaning they would be removed from shared classes and other shared environments. Basically, we have the right to safe and equal education free from sexual harassment.”

Of course, this knowledge is largely limited to students in such elective classes, leaving many others unaware of the protections available to them.

But the kind of leadership Berg spoke about demands relentless action to uphold student safety and protection. Title IX’s enforcement depends on awareness, accountability, and action. The question for LCPS is not whether it follows Title IX — it’s whether it leads the way in ensuring that its students, teachers, and administrators understand what the law requires and why it matters. “I truly believe that [the] first step in the fight for equality and against injustice and oppression [is] knowing there’s an issue [and] knowing you have a right and have options,” Berg said. “Put the advocates and activists and women leading the way in front of you because it can be daunting, and it seems like, ‘What do I do? What hope is there?’ [But], again, you are the majority. You just have to fight.”

For students or parents seeking to report discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual violence, or a Title IX violation, resources are available:

LCPS Title IX Coordinator: Christopher Moy – [email protected] | (571)-252-1548

LCPS Title IX Website: https://www.lcps.org/o/hr/page/title-ix

Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office: (703)-777-1021

National Sexual Assault Hotline: (1-800)-656-4673

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)