English teacher Susan Spengeman’s work is easiest to see in hindsight. It’s in the way a new teacher adjusts to their first chaotic September. It’s in the habits that survive beyond a year: how a lesson plan is structured, how a classroom settles into a rhythm, how a bad day is absorbed and moved past. Officially, Spengeman teaches AP English Literature and Composition, English 11, and Fundamentals of Writing at Rock Ridge High School. Unofficially, she has spent years building the conditions for others to succeed — conditions that, once established, are easily mistaken for inevitabilities.

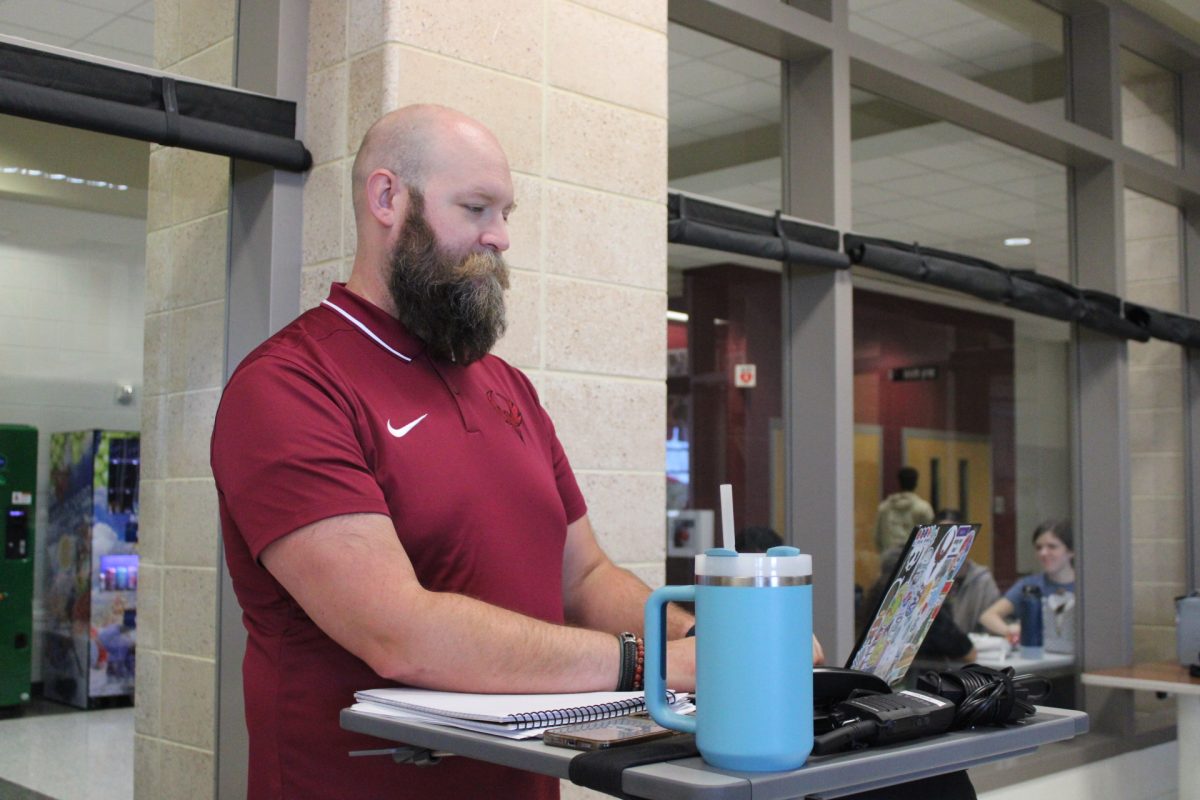

This year marks Spengeman’s first as lead mentor, a role that bridges both the building and county levels. Every new teacher to Loudoun County Public Schools (LCPS) is paired with a mentor, ideally someone teaching the same subject. “Every teacher new to the county or in a new position in the county has a mentor within their building,” Spengeman said. “My job as lead mentor is I basically help organize that. I’ll get the names of all the new teachers, then [I] work with the department chairs to get the best possible pairing.”

The work is not glamorous. It begins each summer, hunting down new hires who don’t yet have school email addresses, chasing personal contact information, and pairing them with the right mentor before they’ve even stepped into their classrooms. It continues all year with monthly meetings designated not to overwhelm but to ground. “The purpose of the lead mentor meetings is to build school community,” Spengeman said.

The structure matters, but what most people remember isn’t the calendar or the logistics. It’s Spengeman herself.

English teacher Shelby Whittington joined Rock Ridge in 2014 as a first-year teacher and recalled Spengeman’s foundational mentoring influence. “She was the first person to share materials and things that she’s built,” Whittington said. Whittington also expressed that much of her own classroom structure — including rotating group activities and first-day procedures — came from Spengeman’s guidance. “She absolutely goes above and beyond for her students,” Whitington said. “If she doesn’t get things done, she takes it all home and she’ll spend so much time on them.”

Spengeman also co-leads the county’s Beginner Teacher Cohort for secondary English teachers, a program launched just two years ago. The program, similar to her lead mentor role, pairs first-year teachers with veteran coaches and focuses on not just on instruction but survival: helping teachers navigate lesson planning, student engagement, and the quieter logistics of professional life. “We [host] some speakers, and another second English teacher and I lead [that],” she said. “It’s about building community and helping them prepare for teaching.”

English teacher Jordan Zapp, who attended Spengeman’s county cohort sessions, remembered how Spengeman modeled effective teaching even when addressing colleagues. “She would run our teacher trainings like her classroom to give us a sense of her teaching style,” Zapp said. “She’s so engaging and she really is organized and you can tell she puts so much effort into her lessons in a way that it’s impossible for students to fail.”

While the county-wide program offers teachers resources and strategies, it also is a space to ask questions they might not even know they had yet. “Teaching is a hard profession,” Spengeman said. “If I ever say ‘I know everything,’ I need to retire because [I’m] not being a good teacher.”

Yet she speaks equally honestly about the demands of the job, and the need to recognize when enough is enough. After years of leading departments, advising student publications, and training new teachers, she deliberately stepped back for a time to recalibrate. “I said no to everything for a period of time, which actually was very beneficial,” Spengeman said.

Spengeman has passed on her beliefs to those she trains, evident in English teacher Daryn Lewis, a new teacher this year. “One thing that I will always take from Ms. Spengeman is just to not take things too hard,” Lewis said. “We’re juggling so many things at once, if we let every mishap guide us, we’d all have burnout.”

And Spengeman knows the math of burnout intimately. But she is also clear-eyed about the systemic pressures facing teachers today: long hours, bureaucratic instability, the expectation of self-sacrifice. Next year, she’s planning to step down from the county cohort to focus more fully on Rock Ridge mentoring. It’s a decision both practical and philosophical. “You don’t sacrifice yourself for your job,” she said. “It’s an important job, yes. But you also still need to pay your mortgage.”

What Spengeman tries to pass on to new teachers is not perfection but endurance — a long view of a profession that can be both meaningful and structurally exhausting.

“It’s all going to be fine,” she said. “And if you have a bad day, it’s fine. You’ll figure it out.”

Part of mentoring, she believes, is giving permission: to vent safely, to ask for help, to resist the corrosive pressure to pretend everything is under control. “Find people that you can vent to and have it be safe,” she said. “Because we’re not allowed to say our feelings a majority of the day.”

Her own habits reflect that philosophy. She tutors one night a week. She runs a small cookie company on the side. She still reads contemporary poetry for herself, still experiments with new teaching methods after 20 years in the classroom.

“She’s got range,” Zapp said. “She can be so serious and into a text, and she’s so intelligent — and then she’s also hilarious.”

At Rock Ridge, and throughout LCPS, where turnover is high and expectations are higher, Spengeman’s presence is a reminder that some parts of teaching are simple, even if they aren’t easy: Show up. Pay attention. Keep learning. And above all, stay.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

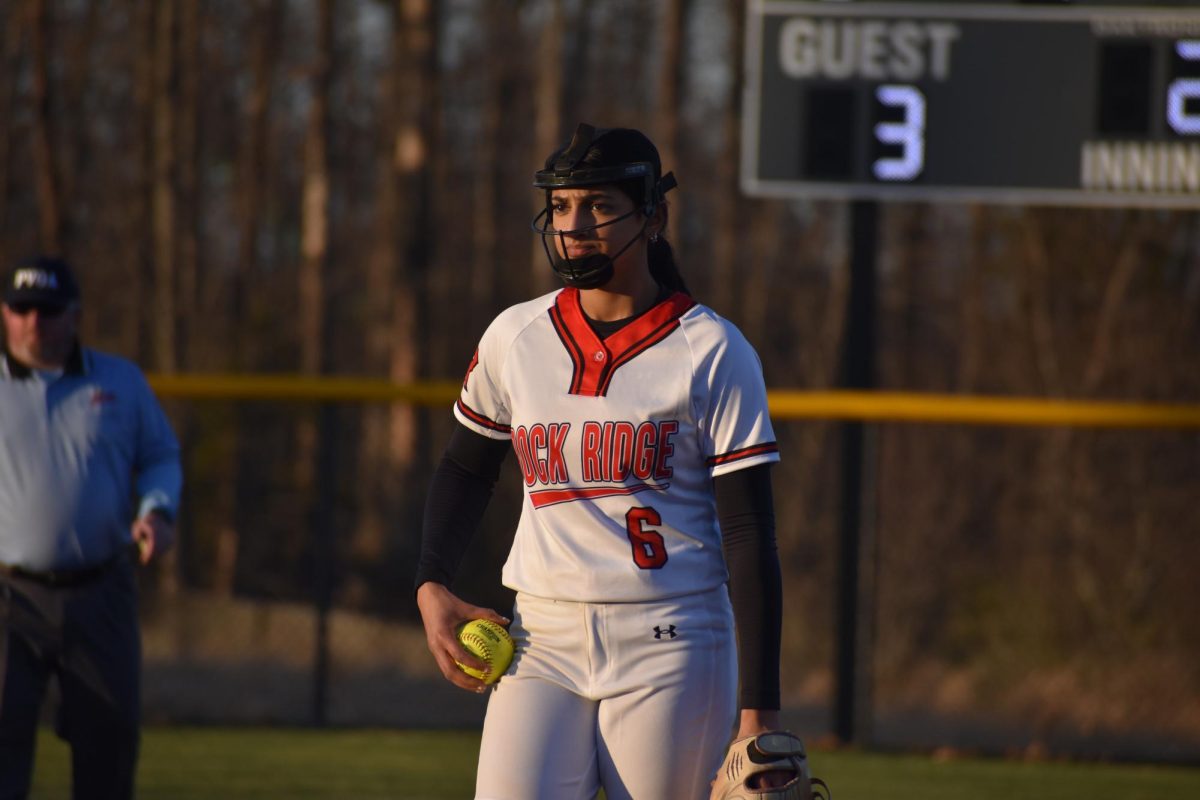

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)