Trust Your Doctor — or Don’t

Should medical malpractice be considered a crime, or will it drive away future patients and prospects from hospitals altogether?

Doctors are held to expectations that are beyond human capability. While most crumble from the stress, some can take advantage of their power over patients and abuse it.

January 28, 2023

It’s 1987, and you’re in dire need of a new heart. A heart transplant surgery has yet to be performed successfully, so you’re at risk to either die from heart complications or by the error of your own doctor.

24 hours later, Dr. Zbigniew Religa took your seemingly unfixable scenario and performed a successful operation. Despite the looming fear of failure, malpractice lawsuits, or having his medical license revoked, he is now considered a pioneer of heart transplantation.

Medical practitioners such as Religa are heroes to their patients, but a victim to strenuous medical careers. Professionals like him must be on the front line for hours on end, exposing themselves to various harmful diseases for up to 50+ hours per week.

For example, the doctor to patient ratio in rural areas is about 262 to 100,000, which is one doctor for every 385 patients. Many of these doctors experience burnout, divorce, substance abuse, psychological stress, and suicide throughout their careers.

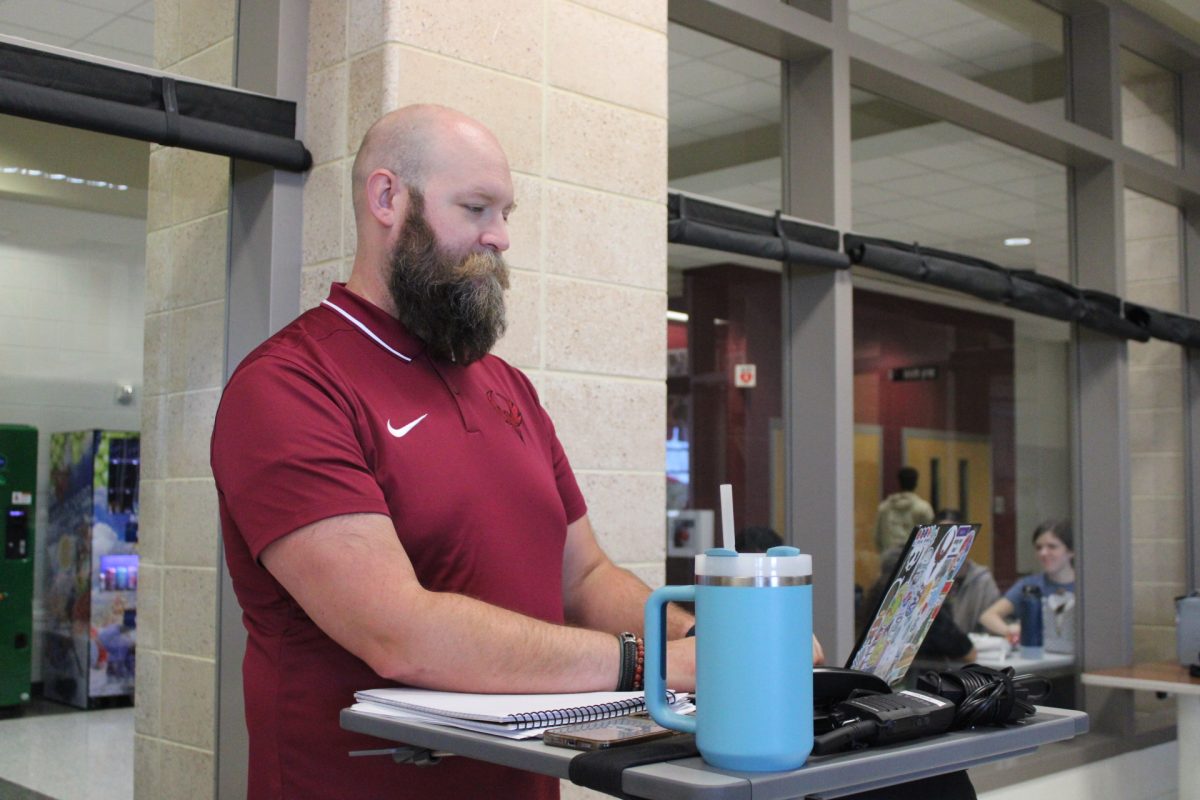

The Administration of Justice teacher at the Academies of Loudoun, Paul McKenzie, agrees that being a medical professional puts you in a very tough position. “On one hand, you are expected to be god-like and inhuman in your perfection,” McKenzie said. “And on the other hand, you are a human being with human vulnerabilities and human cognitive limitations.” Arguably, criminalizing medical errors does not make health care systems any safer; rather, it has the opposite effect upon both patients and doctors. Overwhelming expectations can further damage the mental health of doctors and endanger the patients due to the lack of honest reporting of medical errors. “If we give them an incentive to cut corners because we ask too much of them, we’re going to get a human reaction,” McKenzie said. “If people work a 12-14 hour shift and demand perfection, they’re going to cut corners.”

David Bennet is the first individual who received a genetically modified pig heart transplant. The trial was deemed successful, and increased his lifespan significantly. Medical innovation can be linked directly to this operation. Would the leaders of the surgery have been able to make this shocking discovery if the fear of prosecution were looming? Wouldn’t we all be scared to think outside of the box and innovate?

At the same time, should there be a limit to medical experimentation? From a patient perspective, the answer would be a unanimous “yes.” Imagine having not one, not two, but 93 siblings because of the experimentation of a doctor. How?

Dr. Donald Cline, a former obstetrician and gynecologist conceived numerous children without disclosing himself as a sperm donor to patients. The extensive family tree rallied together to make sure that Cline received proper consequences. Despite mass retaliation by his offsprings and their families, sexually assaulting nearly 100 women, and affecting future generations of children, he only received a one-year suspension. Cline is currently at liberty, free from any incarceration, while more and more offspring are being discovered to this day.

Or rather, picture this: you have been put under the care of Dr. Harold Shipman. Your previous doctor has helped you reach a practically full recovery, and you trust that Shipman will do his job just as well. Unfortunately, this medical professional has a history of injecting his nearly recovered patients with deadly doses of diamorphine. You are now the victim of a serial killer, and are one amongst 250 other patients who were killed the same way. “I don’t think you can serve justice completely; that amount of pain can’t be recompensed.” McKenzie said. “In the next life you get justice, in this life you get law. They’re not the same thing.”

According to Johns Hopkins, 251,000 individuals die from medical malpractice per year, earning itself a bronze in leading causes of death in the US. This rate surpasses cancer, stroke, Alzheimer’s, accidents, diabetes and pneumonia. By criminalizing harmful, avoidable errors, the US can maintain or improve the prestige of the medical field. If we don’t hold hospitals and doctors to a higher level of accountability, some argue, standards are guaranteed to plummet, along with patient trust in the healthcare system.

As a member of the Administration of Justice class at the Academies of Loudoun, John Champe senior Michael Oenderman’s background in law and justice allowed him to make several connections to health and medicine.“It’s like if law enforcement said ‘oh I just talked to him and then pulled out a gun,’” Oenderman said. “You want to make sure that care and use of force are up to par.” Excessive use of force can be deadly in any “god-like” profession, where the life of one is in the hands of another.

Although holding doctors accountable for their mistakes would increase trust within practices, ultimately, doctors lose crucial learning opportunities that may help them resolve underlying system failures that allow these errors to occur. Medical students also lose the opportunity to develop a love for the career, as the fear of lawsuits and being put out of a job will shoo away future prospects.

The line between mistakes and malpractice can be blurry. Religa couldn’t have performed the first heart transplant without acknowledging the possibility of error, while Cline should have faced harsher consequences since his “error” was not a mistake, but was certainly malpractice. But even if the case isn’t always so clear, doctors should be given room to make mistakes. “I think mistakes are inevitable, but medical error is something that should be overcome,” pharmacy technology teacher Ashley Reid said. “Science is made by mistakes, unfortunately.”

Controversy surrounding these subjects pulls professional opinions in both directions. This tug-of-war has both allowed and prevented certain death. The indecisiveness of a god-like profession can alter a patient’s fate, the uncertainty resulting in a living feat or a perished victim. The power should lie with the patient, not man-made gods. The life of the patient is a priority, and any medical professional who sees otherwise is nowhere near celestial.

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)

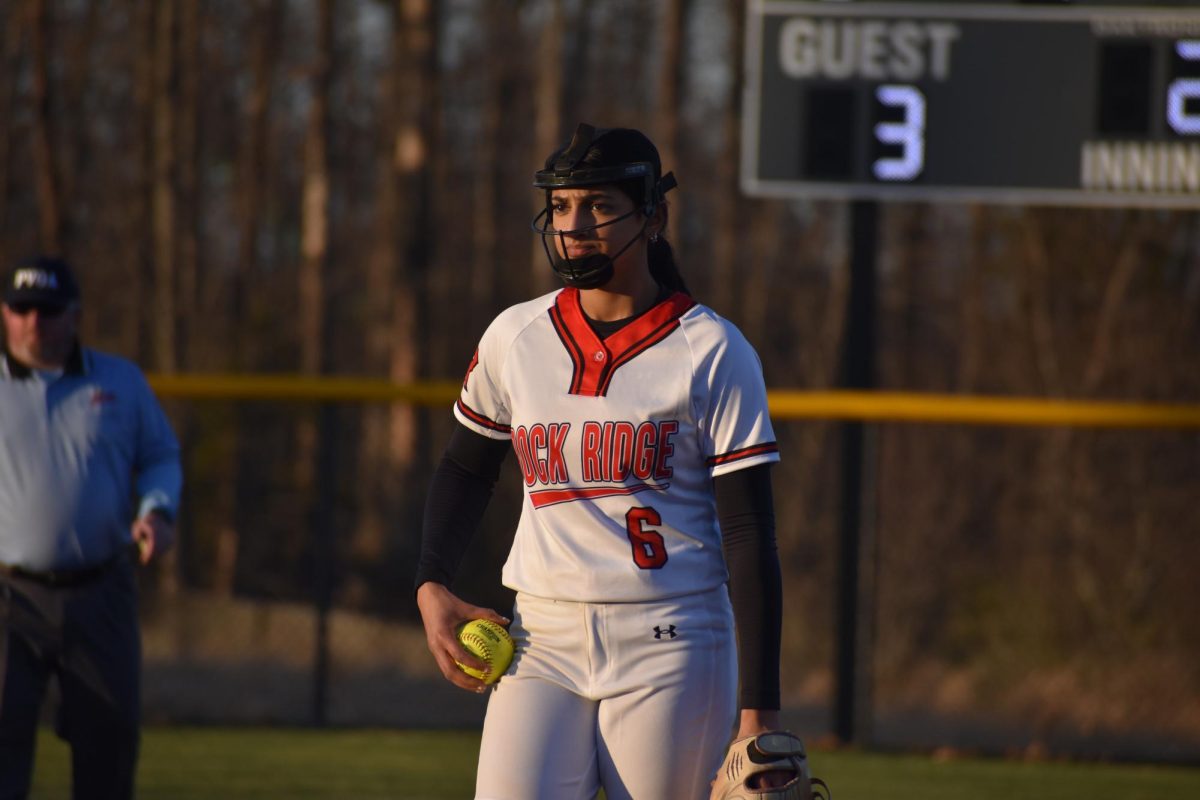

![Junior Alex Alkhal pitches the ball. “[I] just let it go and keep practicing so we can focus on our goal for the next game to get better as a team,” Alkhal said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DSC_0013-1-1200x929.jpg)