In just eight weeks, the sequel to Disney’s “Moana” made over one billion dollars. The film premiered at the Lanikuhonua Cultural Institute in Kapolei Hawai’i with traditional Polynesian dancers and a dub of the movie in Indigenous Pacific islander languages to celebrate Polynesians and the spread of their stories. But why is there such celebration over this film?

It is because many Polynesian peoples depicted in the film, including the people of Hawai’i, have fought for tens of years to keep their native cultures alive. Many of the cultural features in “Moana 2,” such as traditional dances, communal song, and conch shell symbolism began their cultural revival as late as 1970, during Hawai’i’s Second Renaissance period, in which Kānaka ‘Ōiwi, or Native Hawaiians, made efforts to revitalize and recover from Americanization and forced assimilation.

The representation and acceptance the films have brought is treasured because of the long fight it took to get that recognition.

History

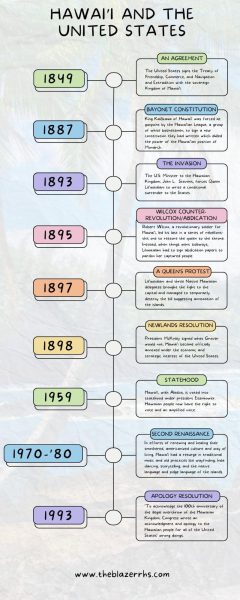

For the first 66 years of American occupation, the nation of Hawai’i was unconstitutionally claimed without the say or consent of the governed.

The first major conflict began when white businessmen in an economic group called the Hawaiian League forced King Kalākaua to sign a constitution of their interests at gunpoint. Now known as the Bayonet Constitution, the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawai’i greatly diminished the authority of both the king and his people. When the king died shortly after, his sister Lili’uokalani took the throne. When Queen Lili’uokalani tried to bring power back to the Hawaiian people in 1893, United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom, John Leavitt Stevens, staged and enacted a coup d’état against Her Majesty in what Congress’ Apology Resolution referred to as an “illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy.” He and his supporters demanded the Queen secede from their provisional government, and in avoidance of further bloodshed, she temporarily yielded to the United States her power as monarch. No later than two years did the Queen formally abdicate in exchange for pardons of her people who fought in the Wilcox Counter-Revolution.

The former Queen almost managed to win back her nation with Grover Cleveland in office, and again when she and her people petitioned against the official annexation proposed by President William McKinley, the Spanish-American encouraged McKinley to propose annexation, this time with stronger greed for land and oceanic power. McKinley’s second attempt at annexation was a success, no matter what the people of Hawai’i said, they were now on American soil. Already, the provisional government had banned Hawaiian medium education in 1896. Much like mainland Native Americans under colonization, Hawaiians faced the endangerment and suppression of their culture under industrial, Americanizing schools and harsh judgment of native practices.

The Progress So Far

After Hawai’i had fought for and acted as a crucial military base for the United States during both world wars, statehood had been long awaited by the people of Hawai’i, they wanted a vote; they wanted a say in what had become their country. In August of 1959, President Eisenhower gave them that anticipated option, and Hawai’i became the last state added to the Union. Hawai’i had gotten some sovereignty back.

It wasn’t until that second Hawaiian Renaissance period in the 1970s that, while the mainland was dealing with its own political upheaval and protest sparked by the Vietnam War and the Watergate Scandal, the Kānaka ‘Ōiwi were able to focus on themselves and taking their livelihoods and ancestral practices off of the down-low life support carry-down culture it had been forced under.

After 100 years of dominance in Hawai’i, Congress wrote Public Law 103-150, formally apologizing to the Native People for all the United States had done, and expressed its newfound commitment to reconcile with the Hawaiian people. Ever since Bill Clinton approved the legislature, the federal government has worked with several Hawaiian agencies to subsidize power and sovereignty to the islands.

What’s Left to be Done?

Although much progress has been made regarding Hawai’i and its ancestral values, there are still many protested plans and events that use Hawaiian soil. Many Native Hawaiians still stand against the militarization and industrialization of the state, for example, the RIMPAC war exercises, and the proposed Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) to be built on sacred land.

There is much to be done for the independence of the Hawaiian Nation, but for now, the pleas of the people, including Moana’s voice actor Auli’i Cravalho, is to treat their home with respect. In an interview with Blavity TV, Cravalho explains the housing crisis and gentrification Native Hawaiians face.

“Go home. You can come and visit, but we are sadly being priced out of our own paradise, it’s too expensive for me to buy a home here for my family,” Cravalho said. “We want to live here ourselves. Keeping that opportunity open for Native Hawaiians would be great.”

![French teacher Marieme Toure serves a plate of the Senegalese food she prepared for her AP French Language and Culture class, to senior Faiza Syed. “I never had Senegalese food before,” Syed said. “I thought it was so cool that she was able to bring a part of her culture [and] background to us.”](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_0798-1200x906.jpeg)

![The Phoenix varsity volleyball team lines up for the national anthem. “We were more communicative [with each other] during this game, and I feel like we kept our energy up, especially after the first set,” senior Jessica Valdov said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DSC_0202-1200x800.jpg)