The Leak Week’s Trickling Effects: How Menstruation Impacts Students

For centuries, menstruating individuals have been taught to keep quiet about their monthly visitor, but the struggles they face continue to affect millions around the globe.

From the invention of the first menstrual products, which included rubber and aluminum menstrual cups in the late 19th century, to current innovations like washable menstrual pads, menstrual supplies have greatly evolved. Yet, countless menstruating students still go without access to these essential items, experiencing the constant taboo and intense symptoms associated with menstruation.

About once every month, many face the same bloodred, sticky fate—the dreaded “leak week.” But she must keep quiet or else she might kill the wheat and caterpillars, as well as blacken clothes—or even harm her husband due to her radiating impurity.

In the late B.C.E. and early C.E., this was the commonly accepted narrative that Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and philosopher, and the Book of Leviticus, written by Moses, believed and circulated. More than 2,000 years later, the basis of this misogynistic narrative remains, and menstruation continues to be a taboo topic.

Aunt Flo’s Embarrassing Quirks

Today, this taboo around menstruation persists. In many rural Indian communities in Nepal, for example, the practice of chhaupadi is widely used. This ancient tradition bans menstruating individuals from participating in public activities. They are banished to sheds outside of the house for the duration of their period due to the fear of them giving bad luck to their families. Young girls even die due to these “menstruation huts;” it was calculated by the University of Bath and the Center for Research on Environment, Health, and Population Activities researchers that 60% of girls in the study knew the illegality of the tradition, yet 77% still practiced (or are forced to adhere to) it. The exact number of deaths caused by chhaupadi are not known, but countless individuals are reported dead because of it every year.

Other cultures around the world also face difficulties in overcoming traditional values and deeply rooted superstitious beliefs. In many communities within Senegal, menstrual blood is viewed as an “impurity, filthy, [and] evil substance.” In the Far West, many fear that a particular God or Goddess “may be angered if the practice is violated, which could result in a shorter life, the death of livestock or destruction of crops,” according to a 2011 U.N. report.

Yet, menstruation is a widespread and natural phenomenon that 1.8 billion people around the world experience every month, equating to about 26% of the world’s population. Within the U.S., 800 million individuals experience menstrual cycles every day. There are a variety of factors that influence how individuals deal with and experience this time—including symptoms, access to supplies, and the taboo that surrounds the topic—which in turn affects their daily productivity and quality of life.

For students, these challenges persist, particularly as it relates to their academic performance. Some miss school days entirely due to the symptoms, while others miss parts of their day as they go to the school nurse, Robyn Wisti, for assistance. “Sometimes, I go to the nurse, so I miss classes,” junior Mai Dorgham said. “When I go back to class, I know that the stuff I’m missing, I have to make up on the weekends or when I go home.”

Many students have also noticed the stigma around menstruation and the awkward discussions that often come up. “I have definitely noticed a stigma around menstruation at school,” junior Neha Bhusarapu said. “It’s kind of an awkward topic to bring up and something that makes people feel ashamed, because it’s hard to talk about.”

Freshman Kaavya Borra has noticed that menstruation is an awkward subject to discuss, but not around friends. “I think with your friends, [the topic is not really taboo], but I wouldn’t just go up to some random guy and say ‘I’m on my period, give me food,’” Borra said.

English teacher Jennifer Beasley also struggles with dealing with her menstrual cycles at school. Teachers are given ten days of paid sick leave per school year, and Beasley finds that it is impractical for her to be absent from school two to five days every month.“It’s hard, it’s painful, and having gone through [menstruation] for the past 20 years, I feel like it’s something that girls are just expected to deal with and not talk about,” Beasley said. “The expectation is that it’s hidden, [but] it’s not comfortable to have a paper cut that is bleeding non stop. I feel like it’s another example of womens’ strength.”

The expectation is that it’s hidden, [but] it’s not comfortable to have a paper cut that is bleeding non stop. I feel like it’s another example of womens’ strength.

— English teacher Jennifer Beasley

Crimson Tide Stains on Academics

Many students experience premenstrual syndrome, which is a condition that precedes menstruation, bringing about 75% of menstruating individuals various symptoms including fatigue, nausea, back pain, abdominal cramps, and decreased productivity/attention span. For some students, the pain is so severe that it causes them to miss school, work, and important exams. According to a study published in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, more than 33% of young girls have missed at least one class in the past three months due to “menstrual symptoms.” This greatly affects individuals’ academic performance and chance for growth, as students are often left catching up on old information.

Sophomore Dora Akouete said that she often is not fully focused in class when on her period due to the severe symptoms. “Sometimes I’m sitting in class, and I can feel the cramps, and it’s hard for me to focus, because I’m worrying about when this class will end to go find someone who can give me medication to get me through the day,” Akouete said.

According to a study published in BMC Women’s Health, “48.1% of students with mild PMS symptoms and 51.9% with moderate or severe symptoms often or always missed school because of their symptoms.” This repeated absence of menstruating students not only leads them to miss school and socializing with friends, but also emphasizes the prevalence of the issue. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has said that heavy periods and associated symptoms “can disrupt your life and may be a sign of a more serious health problem;” normal periods should not interfere with daily life activities and “living your life to the fullest,” like attending school.

However, normal discomfort is usually expected, and health professionals believe that individuals should be accommodated accordingly. If students experience discomfort at school, Wisti allows for them to use heating pads in her office and take a break from their work. The clinic no longer offers acetaminophen available to students, but parents can provide medication to the clinic for their students to utilize during the school year. If medication is unavailable, students are offered time to rest, according to Wisti. “If medication is unavailable for a student, I offer the student about 20 minutes of rest with the heating pad,” Wisti said.

Research conducted by the British Medical Journal in 2019 showed that 13.8% of women aged 15-45 years from a 32,748 sample size were absent from their workplace during menstrual cycle, with 3.4% reporting absences “almost every menstrual cycle.” Overall, a 33% productivity loss was noted, calculating to 8.9 days of productivity lost per year. Yet, when reporting this information, only about ⅕ of women attributed their absenteeism to menstruation, and nearly 70% wished for “greater flexibility in their tasks and working hours” during their periods.

Wisti said that open dialog is the key to ensuring students’ success. “Menstrual cycles are a part of life, and I feel it is important for students to have an open dialog with their teachers and be honest if they are unable to complete assignments due to their mood or pain,” Wisti said.

Not Enough Shields Against the Red Baron

Another key consideration that complicates the process of menstruation for students is the lack of access to proper supplies and resources as well as menstrual education, also known as period poverty. According to Feminism India, ‘rags, hay, sand and ash’ are used in place of sanitary pads and tampons in India; these substitutions are often unsafe and can lead to further problems and complications.

In low-income areas like Latin America and the Caribbean, individuals have had even less access to hygiene supplies due to the impacts of COVID-19. The pandemic has exacerbated period poverty around the world, with community health centers and schools being closed as well as supply chain issues, ridding many of free access to hygiene products.

Specifically in the U.S., it is estimated that 25% of students who menstruate do not have access to proper sanitary supplies. Damaris Peredea, the national director of PERIOD, a nonprofit organization that focuses on service, education, and advocacy of menstruation, said that students who menstruate should be provided with sanitary supplies just as students are provided soap and water in bathrooms. “This country already expects schools to provide toilet paper and soap,” Pereda said. “[Why shouldn’t students who menstruate have the same access to basic supplies], so that if something happens, they can just go to the restroom and get their things and continue to live their lives?”

This problem is further aggravated by the pink tax, more specifically, the tampon tax, which is a popular term used to describe the sales tax placed on tampons and similar menstrual supplies, while other personal items are sold without them. Existing in 30/50 U.S. states, this tax makes it harder for the 12.8% of menstruating individuals who live in poverty to access necessary hygiene products.

Teachers at Rock Ridge believe that these taxes only further prevent individuals from receiving the necessary menstrual supplies they need. “It’s a tax that essentially says ‘this product is not a necessity, it is a luxury,’” English teacher Jessica Berg said. “[The tampon tax] disproportionately affects communities of color [and those with] low socioeconomic groups, and the majority of students miss school because of [the lack of] access to resources.”

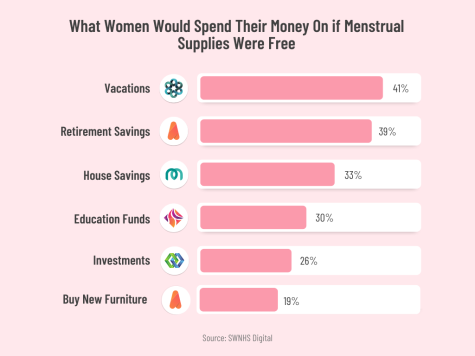

Tax policy encompasses state and local/county funding—by working to eradicate the tampon tax, some consider that the Va. government is infringing on their right to make their own decisions. One of the main arguments of those who oppose improving menstrual equity is that adjusting the price of and taxes on menstrual supplies is infringing on the localities’ right to set prices and regulate their local government. Women in the U.S. spend an extra $150 million on menstrual products due to the tampon tax, which is another way of revenue collection for states. Yet, Berg believes that this revenue can be generated in other ways, especially as the tampon tax has been abolished in states like Alaska, Florida, and California.

Va. Senator Jennifer Boysko (District 33) acknowledges the disparities and lack of menstrual equity in the country, saying that it is time to put age-old stigmas aside and address the problem head on. “Some girls don’t have access to supplies, and it keeps them from being able to go to school or do regular things,” Boysko said. “Instead of acting like we should be ashamed of this, I think it’s important that we talk comfortably about it and provide those resources for those who don’t have access to them.”

In an effort to bridge this gap, Boysko sponsored the Dignity Act, which aims to implement a “reduced rate on essential personal hygiene products.” According to Boysko, the bill was passed, but a portion of the local tax was left on the products to ensure that localities still possessed tax authority. This year, Boysko is working to completely eliminate the taxes on menstrual supplies with another bill, but it was grouped into the broad category of eliminating grocery taxes, which makes the issue a “bit more complicated.”

Boysko said that her inspiration and drive to improve menstrual policy stems from the fact that women don’t have a choice to have menstrual cycles and purchase the necessary resources. “Women don’t have a choice of whether or not they want to buy [the products]; it’s an essential product,” Boysko said.

Specifically, in schools, the Va. government has made strides in ensuring students have access to menstrual supplies while at school. On April 6, 2020, Gov. Ralph Northam approved Senate Bill 232 with “broad support” from the legislators; the bill mandated that Va. schools provide free menstrual supplies to students in bathrooms.

Nonprofit organizations have assisted in providing schools with the necessary supplies to keep bathrooms stocked. Specifically, Bringing Resources to Aid Women’s Shelters, which is an organization that works to provide menstrual supplies and undergarments of women in need, supplies LCPS schools with the period products on an “as needed basis.”

In addition to the support of BRAWS, at the start of the 2021-2022 school year, Berg began to stock the English hallway bathroom with menstrual supplies using her own money. “This is a teaching profession, which tends to have a lot of women, so I just decided to start stocking our bathroom with menstrual supplies and other things like lotion and hairspray, because inevitably [people] will be teaching during the day, and they’ll run to the bathroom and say, ‘Oh no, I started my period,’ and [the supplies are] just right there; you don’t have to run back to the classroom,” Berg said.

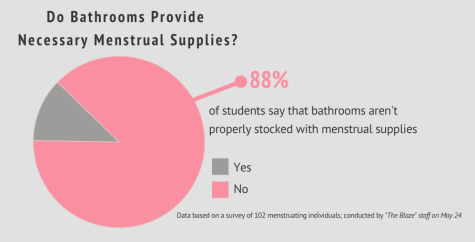

Though LCPS schools sometimes have bathrooms stocked with feminine hygiene products, many students find that either all supplies are finished or only pads or tampons are available, limiting students’ options. In a survey of the school’s female population, 88% of students responded “no” to the question of “does bathrooms have the menstrual supplies you need.” Though the student and staff bathrooms are stocked by BRAWS and Berg, they are more often than not empty, leaving students to ask friends and classmates for supplies or visit the nurse’s office, a task that can be embarrassing for students, partly because of the shame associated with the topic.

Attempts to Normalize Mother Nature’s Undiscussed Gift

At Rock Ridge, some students have tried to eliminate the stigma that exists around menstruation as well as raise money and gather supplies for the underprivileged, who lack access to pads, tampons, and menstrual education. Ms. Phoenix, a club run by Co-Presidents junior Bhusarapu and senior Shriya Ravikanti, focuses on empowering women through raising awareness and fundraising for causes including equality, women in the workplace, and menstrual health. Ms. Phoenix, sponsored by Berg, also runs their annual “Rise To” Summit, where community leaders come together to discuss their experiences and perspectives regarding various issues affecting women including gun violence, voting rights, and reproductive rights.

Bhusarapu said she loves the club because of the community and bonds that the club allows members to create. “I’m passionate about it because I like what it stands for; it’s not only a club where people can get hours and opportunities, but [it is also] more of like a community and a sisterhood bond where all the girls come together,” Bhusarapu said.

Throughout the past few years, Ms. Phoenix has worked to help donate menstrual supplies to those who need them, including a hygiene drive in which they collected pads, tampons, and other menstrual products to donate to a local non profit organization, Mobile Hope.

In an attempt to help lessen the taboo around menstruation, some teachers also have stepped in to create an environment in which no student feels judged and guide students through this uncomfortable time. Beasley said that there have been a few instances in which she has had to show students how to use menstrual products like tampons. “Me and a couple of other teachers have had to explain [how to use menstrual supplies] to students who don’t even know how to use the products; they’re too afraid to use them, they don’t know who to talk to about it, and we’ve had to help students through it occasionally.”

Despite efforts by students and teachers, menstrual education and acceptance is still sparse at the high school level, especially among those who do not menstruate. A contributing factor to this problem may be be lack of access to sexual education in schools, specifcally in Family Life Education. Also known as FLE, this Virginia-wide program provides sexual education to students who are opted in on topics such as the benefits of postponing sexual activity, relationships, and abstinence education.

The curriculum for girls also targets the menstrual cycle and how to prepare and handle it, starting as early as 4th grade. This allows for students to prepare for periods before they come and be educated on the mechanism and reason for them. However, this education is largely focused towards girls, which prevents boys from being educated, contributing to the stigma around menstruation.

Boysko is unfamiliar with the specific menstrual education provided to boys in elementary and middle school, but she believes that it is a “good idea for boys to have access to the same information that the girls have.”

Even at the highest levels of state government, Boysko has noticed that, while most menstrual policy has received “broad support,” she has witnessed hesitation around menstrual policy due to the taboo nature of the topic, specifically among her male colleagues. “I can remember that my colleagues, who were men, were dismissive and embarrassed,” Boysko said.

Many students also agree and said that boys’ awareness on this topic would allow them to slowly break down the stigma that exists around menstruation. “They should be educated enough to know what happens, why it happens, and how they should act towards it,” Bhusarapu said.

Junior Shiraz Amiri, who identifies as a male, also believes that boys should learn about menstrual cycles, so they can assist those who experience menstrual cycles. “I honestly believe that [boys] should be educated about menstrual cycles, more for understanding what [the girls] need and [what they go through],” Amiri said.

In recent years, strides have been made to increase access to menstrual supplies at school and decrease the stigma associated with the subject through students advocating for change and increased protective legislation, but questions still remain on how this stigma can be eliminated once and for all. “I don’t have the answer [as to how to normalize discussion of menstruation]; I think I’ve been indoctrinated and inculcated to shove a tampon in my sleeve, make sure I take Advil, and get through my day,” Beasley said. “I don’t know how to change [this stigma] or what the right way to change that would be.”

A senior at Rock Ridge, Nanaki loves everything reading, writing, and calligraphy related. She has a great passion for service and currently serves as the president of Key Club and SNHS as well as the...

![Standing center stage, senior Ananya Akula conducts the Phoenix Chorale. “[Conducting and teaching] is really fun,” Akula said. “Music education is what I want to do.” On the day of the choir assessment, Akula found out that she received the President’s Music Scholarship – a full ride to the University of Miami Frost School of Music.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ananya-1200x800.jpg)

![With the energy and effort the Bolts were bringing to the game, the Phoenix had to step up and match them to make it through their first game of the season. Many of the girls on the team, including freshman Nazly Rostom, have been playing soccer since their childhood and have grown a love for the sport as a result. “It was fun to see how we actually played in a [real] game,” Rostom said. “Even though the outcome was not what we were hoping for, I’m still happy we got to play together.”](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DSC_0154-1200x800.jpg)

![Held up by a group of cheerleaders, flyer sophomore Leyu Yonas poses as part of a stunt, also supported by flyer junior Shayne Mitchell behind her. (Left) Prior to the pink out football game on Oct. 13, the athletes practiced in the aux gym from 5 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. (Right) On Oct. 19, the cheerleaders competed in their District Championships at Woodgrove High School. “We definitely put all our effort on the mat [at Districts], and it showed,” Mitchell said. Left: Photo by Nadia Shirr. Right: Photo by Steve Prakope via Victor O’Neill Studios.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/feature-image-1200x823.png)

![Sophomore Xavier Smith (6), the Phoenix quarterback, runs the ball as his teammates help hold up the defense. “My [offensive] line collapses, so I just [have to run], and its a good way to get first downs because [Tuscarora’s] defense was really good,” Smith said.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/IMG_5383-1200x897.jpg)

![As the referee throws the ball up for the tip-off, freshman Simone Diby leaps towards the ball to get it in Phoenix possession. Diby is a new member of the Phoenix girls basketball team, and despite it being a change, she finds it enjoyable. “It’s definitely a different experience if you’ve never played on a team, [but] I think it’s still fun.”](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/DSC_0057-1200x662.jpg)

![Standing center stage, senior Ananya Akula conducts the Phoenix Chorale. “[Conducting and teaching] is really fun,” Akula said. “Music education is what I want to do.” On the day of the choir assessment, Akula found out that she received the President’s Music Scholarship – a full ride to the University of Miami Frost School of Music.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ananya-600x400.jpg)

![Senior Fatima Qaderi grew into the person she wanted to become when she was younger and continues to work towards growing more confident in using her voice when it matters. “I didnt get treated the way I wanted to be treated, and I realized that it wasnt just them treating me the wrong way, it was me treating me the wrong way,” Qaderi said. “I forced them to like to look at me in a way where Im someone who needs to be respected; they cant just disregard me, they cant just look over me because I have a different opinion, because Im a woman, because Im Afghan, because Im Muslim, or whatever. It just took going through different experiences to figure out how [I wanted to] be heard.” Photo courtesy of Fatima Qaderi.](https://theblazerrhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_3870-600x471.jpeg)